A Story About Students Who Shared What Was Meaningful to Them

And also a story about a teacher who not for a second took the privilege of encountering these sharings for granted.

I want to share a story about our classroom.

Not an anecdote leading into a strategy or resource; and not a story introducing or even disguising some pedagogical viewpoint.

Rather, I just hope to share how this school year, my twelfth in the classroom, came to a close—and why even a week later I am still very much trying to sit with that ending.

What it means to me. What I will take from it.

And perhaps what you might take from it as well.

Task: “Write Something Meaningful”

The final project of our AP Literature course asks students to respond to a very straightforward prompt: write something meaningful.

The only constraints they have to abide by are as follows:

Early on in this process, the most common wall students encounter is a rather-important one, I point out to them, in that they aren’t sure how to express what they find meaningful.

“That seems like a pretty worthwhile thing to figure out,” I offer.

Lots of heads nod in response.

The next few weeks then move through a sequence I’ve watched for three years now: students find a starting point and launch from there; encounter myriad walls when figuring out what and how to synthesize with their starting point; share their ideas during a mid-way workshop and build momentum from the encouragement of peers; and then make that final push until I have at least eighty different projects submitted at approximately 2,024 words a piece.

Then I begin reading.

Students Find Meaning In So Many Places

I’ve reflected before here about my process grading student writing, but this particular experience is a very different one for me as a teacher.

Though it takes place in that final, exhausting stretch, the experience of opening up and discovering what is meaningful to each of these students is, more than anything, a privilege. One I don’t take for granted even for a second.

You see, it is one thing to read these projects as standalone pieces.

However, for me, at this point in the school year, they are very much culminations: of the writing journey each student has been on; of my own observations and appreciations of their role in our classroom community; and of our shared rapport as a teacher and student across a school year. In a handful of cases, multiple school years.

I say it a lot but I don’t say it often enough: teaching can be a really cool thing.

Still, even in the third year of these projects, I’m taken aback constantly by the myriad ways they arrive at what is meaningful to them. Often across different people in their lives, yes, but also so many places and activities—including at our own school.

Theatre. Weightlifting. Soccer. Orchestra. Volleyball. Basketball. Mock Trial. Football. Cross country. Wrestling. Horseback riding. Biology. Leadership. Ballet. Choir. Softball. Culinary. Marching band. Et cetera.

To name just a few.

Encountering these myriad paths to meaning is a humbling reminder for me as a teacher, too, of how much I do not see of a student’s experience and of how fortunate I am to be at a school that offers so many versions of meaning to so many students.

Seriously: reading these makes me very proud of where I work and also very grateful of where I get to work. True, the classroom can be an island, but to realize that your classroom is just one of many in the archipelago of meaning students encounter in their high school experience?

Like I said, teaching can be a really cool thing.

Friendship Is a Through-Line Across The Projects

Still, even across these differences I also have the privilege of seeing several through-lines—perhaps the most prominent of which is how much these students value the friendships in their lives.

In project after project I realize that, even if on the surface it is a project about the meaning they find in various extracurriculars, it so often is really a project by the end about the meaning they find in the friendships around them.

Shared experiences are powerful things, after all.

Amidst a nationwide panic, seemingly, about teenage mental illness and isolation, it is an important reminder for me as a teacher, and then again as a parent, that at the end of the day people very much find meaning in the people around them.

For better or worse, but so often better. Especially teenagers.

The phones do not change that and never did, really, and I can tell you after reading approximately 2024 words in eighty different projects for the third year in a row, that the truest of through-lines has been that these students care deeply about the people around them and that meaning, and meaning-making, is rarely an individual thing.

That makes me smile.

Then I continue reading.

Burdens and Choices Can Be Meaningful, Too

I’m reminded reading these projects that pain can create meaning, too.

This is why reading these projects can also be quite difficult, such as when I come across this line: “I never really knew what identity really meant or was until I realized I had to make a fake one.”

In this moment, I had to stop reading for a bit to sit with the story that resulted in these words being written on the page.

(Note to reader: It’s okay if you want to to pause and consider it, too.)

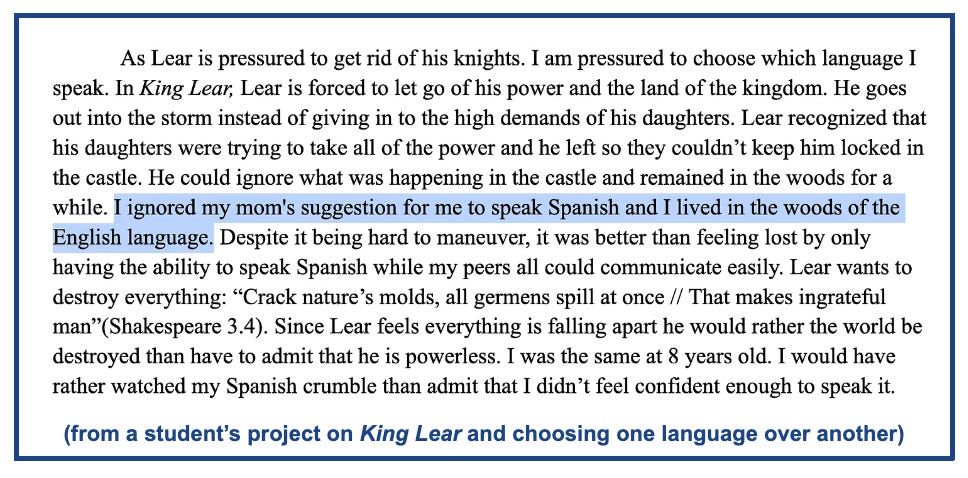

This is also why I ask students to synthesize at least one of our course readings into their projects, and in doing so to experience how they themselves can lean upon the words and stories of others as they work to convey their own version of meaning. For many students, this is the most challenging wall to scale with this project; however, it is also the aspect of the project that so often unlocks a new level of writing and, as a result, meaning.

So I read about the loss of innocence of Myop in Alice Walker’s “The Flowers” through a wondering of what the flowers looked like before she stumbled upon the noose.

I read about what it means to dream for something you’ll never have, as Gatsby did, as well as the Icarus-like euphoria of nearly grasping that dream and whether that “near grasp” can ever be worth the fall.

I read Zora Neale Hurston’s tragic observation from Their Eyes Were Watching God that “all gods who receive homage are cruel” as an introduction into a student’s story about their own father.

And as pictured above, I read perhaps the most profound interpretation of King Lear I’ve ever encountered: “I ignored my mom’s suggestion for me to speak Spanish and I lived in the woods of the English language.”

(Yes, I had to stop reading awhile for this one, too.)

Ultimately, though, in reading all of these stories of the too many burdens students should never have had to bear and the too many choices they never should have had to make—stories that build upon stories of Walker and Fitzgerald and Shakespeare and Hurston, who have created their own worlds and characters and choices to resonate forward over generations—I’m realizing that this is what storytelling is for, perhaps.

An ongoing, shared project of what is meaningful—one that these students are making their own contributions to.

Generously and courageously and beautifully.

Writing can be and should be meaningful, I think, my conviction deepening further with each new project I encounter.

There is a Hope That Can Be Found In Reading

As much as students find empathy in the literature they bring into their projects to reflect on their own burdens and painful choices, they have a remarkable way of finding hope, too.

From the portals of Hamid’s Exit West (see above) to the generational resilience within Gyasi’s Homegoing to the childhood wisdom of Applegate’s The One and Only Ivan—students get to bring in texts from outside the course, too!—students find hope in so many places in a way that inevitably reminds me that hope can be found in so many stories.

One student found such hope in a poem from earlier in our course, “The Leash” by Ada Limón:

As this student rightly acknowledges, on the surface “The Leash” is not a particularly hopeful poem. Yet this student refused that easier interpretation, instead wondering “if they hate people like me” who “think there’s some stupid prospect of hope.”

I read this student’s reflection and I become distracted, thinking of all the times there have been two doors available for me as a teacher—one towards cynicism and another towards hope—and then, stepping back, all the choosing one has to do as a teacher between these doors, the latter often having the much trickier, heavily-rusted lock to navigate as well as much less certainty of what is waiting across its threshold.

To be cynical or hopeful: making that choice so often is really tiring as a teacher.

I turn back to the student’s project.

You just have to look for it, this students ends this section of their project with, an invitation to choose that latter door once more.

So I finish reading these projects and begin setting up for our final class period of the school year.

There is Hope in Teaching, Too

We conclude this course each year with the desks in a circle for the final lesson.

As I’ve shared before, there is a classroom slide deck projected with a one-slide preview for each project when they enter the room. The entire lesson consists of students taking turns explaining what their project was about and what they find meaningful—and classmates taking turns sharing affirmations back to them in return.

I try my best to sit quietly on the outside, intentionally displacing myself so that the circle is entirely their own.

That is how a classroom community should end, right?

Anyways, back to the story.

So it is the final class period of these closing circles and we get to the very last student—and I realize immediately that there is a problem: this student normally sits closer to the screen, but with the circle formation had chosen a seat quite a distance away, which means they cannot read the slide they are trying to share from.

A long pause settles in the room. And then—

“Mr. Luther, I think I’m going to stand up and share from where you typically do.”

What follows (I swear I’m not exaggerating this part): this very quiet student, one who hardly said a word for the first months of the year, gets up and apologetically moves to the front of the the room, and then proceeds to deliver their presentation standing in the “Mr. Luther spot.”

Shakily at first, and then with increasing confidence.

“Part of what I wrote my project about,” they say to their peers, “was you guys. And this class.”

(Note: that is indeed what part of their project was about: finding community in a classroom that they never expected to find community in.)

They keep going, the entire room fully theirs. Applause follows. Deservedly.

I watch all of this happen from outside the circle, appreciating how humbling it is to be in that space and doing everything I can to not forget this moment and what this space feels like before the bell rings and signals the official beginning of summer.

“I don’t know much of anything.”

One student began their project with these six words and I now sort of find myself coming back to them at the end of this story.

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about writing itself and how stories are told through it, including the intentions behind them.

Now that I’m here and the story is complete(-ish?), I do think it is fair to ask myself: what is the purpose of sharing this story here?

In part, it is an expression of gratitude for this amazing group of students, who culminated an already-great school year with one of the best finishes I can remember in my career.

In part, it is a capturing of how I felt in that moment, sitting in my desk for several moments after the bell rang in a silent classroom, clinging tightly before the present tense became past and it would require remembering to be there.

In part, too, I think I’m only realizing right now as I type these words, this almost feels like a living out of the project itself: me trying to express what I find meaningful by building upon the words and stories of these great writers I had the privilege to teach—just as students did with their own projects.

Just as we all do, in the classroom and beyond.

You just have to look for it, that very wise student insisted.

They were right.

This is a stunning reflection on how your students and you made meaning together in a brilliantly built culminating project. Moving, meaningful, resonant. It was so rich and diverse in its insights about children, teaching, writing, and life that I struggle to land on a “most important” aspect. One lesson that feels especially urgent and universal for all of us as educators:

“To be cynical or hopeful: making that choice so often is really tiring as a teacher. I turn back to the student’s project. ‘You just have to look for it.’ This student ends this section of their project with an invitation to choose that latter door once more.”

Thank you for your devotion to child and craft. Truly grateful.

I love and admire how you create community within the classroom and have them get a sense of community outside too. This is also very important for me.

In middle school, we look through everything through the lens of “herd behavior.” When is it necessary to follow the herd? When is it not? We look at all our texts from that lens and at the end their final question is about that and every year I am astounded and fit to burst with hope!

There are days I have left wondering if all the cynical teachers are right! But I, and I share this with my students, I wouldn’t be back if I didn’t love. Love to teach them. Love to see them grow. Love to learn. And have hope.

I do respectfully disagree with your conclusion about phones not having an impact on mental health(and focus etc.) and it’s not necessarily because I feel I am right/you are wrong, but we have different sets of data. Your current AP students would have been in middle school 5 or 6 years ago?

I had those kids.

What I am seeing now is very different. These are not those kids. If that makes sense?

BUT. Hope. Reading your words I have hope that maybe maybe in 4 or 5 years when they become AP lit students (or even the ones who don’t?) will grow and change for the better when it comes to what I am seeing, the isolation and concrete thinking, that’s related to use of phones.

Hope. Or get out of the classroom! 😂