"Challenging Students" Means More Supports, Not Fewer

A reflection on a mistake I made too often around this earlier in my career

I was told that having a four-year-old would be a humbling experience, but I don’t think I was ready for the new tradition my son insists on every afternoon on our drive home from daycare:

“Daddy, can you tell me all the mistakes you made at school?”

A few weeks back we were working on a lesson at home about “being open to sharing your mistakes,” and as of right now the only tangible thing that has come from it is my son’s newfound curiosity in all the mistakes his dad makes in the classroom.

So every afternoon without fail, while his binky-clad younger brother listens with glistening eyes, my son insists that I list off every single mistake I can think of from my day teaching.

Quite a relaxing way to unwind, right?

In the spirit of this incredibly affirming family tradition, I wanted pay it forward by sharing a mistake that I’ve made far too often in my career—and especially at this time of the school year:

Trying to “challenge” students without adequate supports.

(Or even worse: by removing them.)

“Let’s Just Go For It!”

I think many teachers might recognize that urge in the second semester to “mix it up” and “try something new” in the latter half of the year.

Throw stuff against the wall and see what sticks, I’ve often told others as well as myself, knowing that I might learn something in the process that is helpful in future years.

Or then there are those high-flying students who very much deserve to be challenged, and our response as their teacher is sometimes to toss an activity at them last-minute—and cross our fingers it is worth their time as well as our own for them to pursue it.

While these “challenges” for students are well-intentioned, reflecting back I paradoxically feel like they can make the classroom a space in which students are less willing to authentically challenge themselves as a result.

Does that mean you should just stubbornly keep doing what you’re doing and not meet students where they need to be met? Of course not.

But it does mean, I’ve learned, that there are better and worse ways to bring challenge into your classroom—and I wanted to share today about my own three-part evolution in how I think about this now as a teacher:

1. Invest Time in Your Exemplar (or Exemplars)

I’ve long been a fan of teachers taking time to create their own samples of whatever task they are asking students to complete in the classroom. By journeying through the task myself, many times I’ve found myself not only noticing errors in my expectations and instructions but also finding ways to improve the quality of the overall experience. (And building a bit more empathy along the way, too.)

This, then, becomes a clear issue with “just going for it” and tossing a challenge at a student: often times teachers don’t invest the same time or offer exemplars when they do so.

A couple years ago, I had a handful of students who I wanted to offer a challenge to on a writing task at this time of the year, so I wrote up a higher-level path on a whim and offered it to them—and only a couple actually went for it.

The results were less than stellar, and I very clearly one of those students naming it as one of their worst writing experiences of an otherwise-fantastic year.

Reflecting back on that “challenge opportunity,” the lack of buy-in from more students and then especially the negative experience of the couple who did buy-in is 100% a result of my poor planning as a teacher. (Good thing my son couldn’t form complete sentences back then on our drives home from daycare!)

The intention to offer challenge? That was good, and built on not only my own instincts but a recognition of where students were at based on tracking their growth over the previous semester. Students deserve to be met where they need to be met.

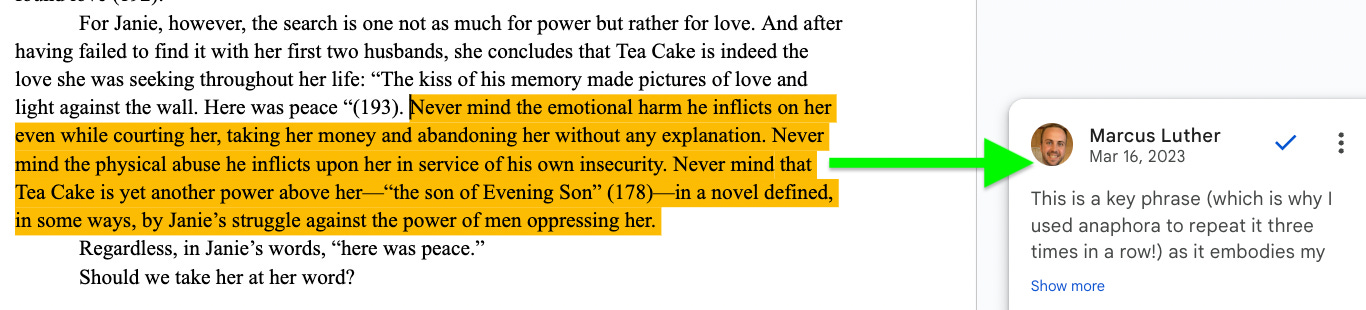

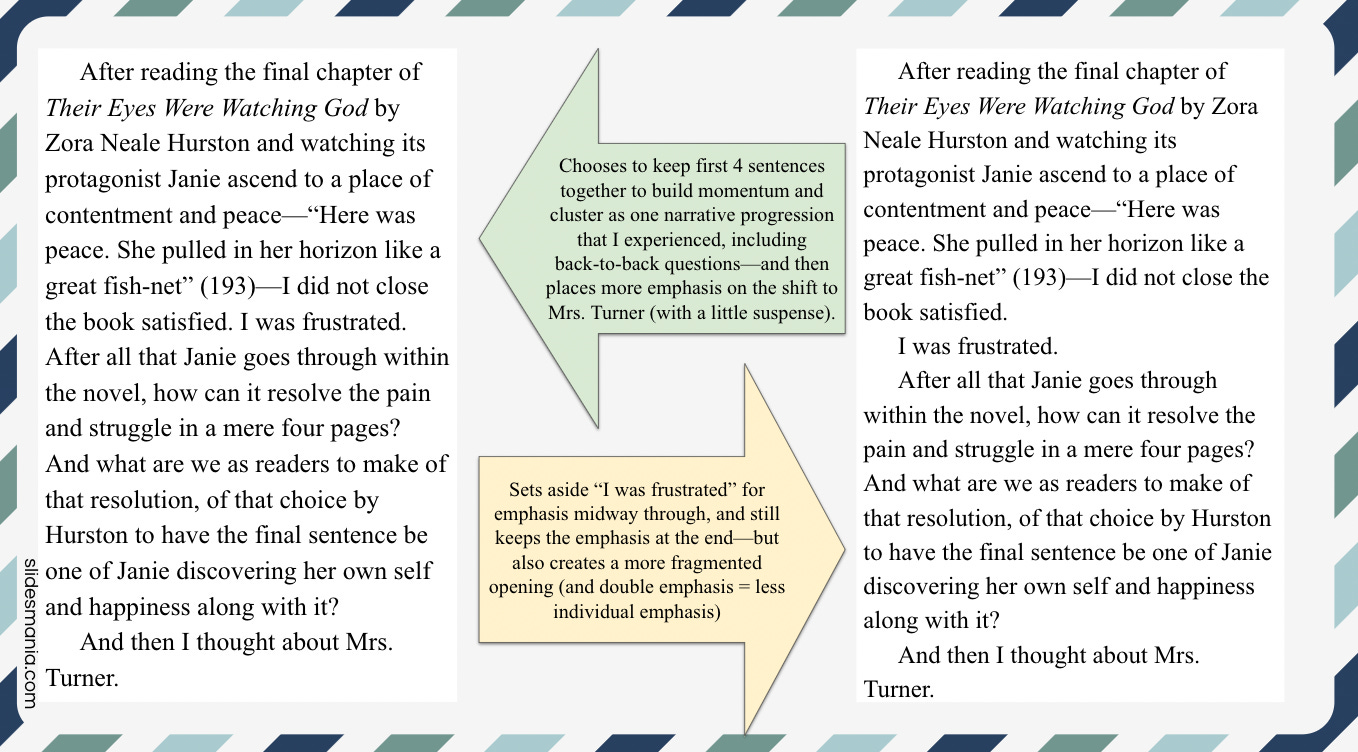

So last year, I took that intention and made an adjustment: investing far more time not only in planning out the “ask” of the challenge but also in creating multiple exemplars they could lean on as writers. I even took it one step further and added in my own reflective comments essentially “annotating the exemplar,” with the goal of making it an even more useful tool than other sample essays:

The goal with all of this investment in the exemplars: making sure that in challenging students I was creating the tools needed for them to access and feel confident in the challenge. And being a major believer in what exemplars can offer to student writers, this became a non-negotiable support to invest in.

2. Backwards Plan from the Challenge Itself

While this challenging writing task that asked students to step outside of the box with their essay structure and synthesize multiple texts went much better last year than the year before, I realized going into this year that my next step as a teacher needed to be backwards planning from the end-result I was asking students to push themselves towards.

Reflecting on feedback from the previous year and the most common obstacles students faced, I was able to not just create tools but more importantly integrate activities and skills into our learning sequence whole-class—shifting the “challenge” from something students pursue and navigate mostly independently into a much more collaborative experience.

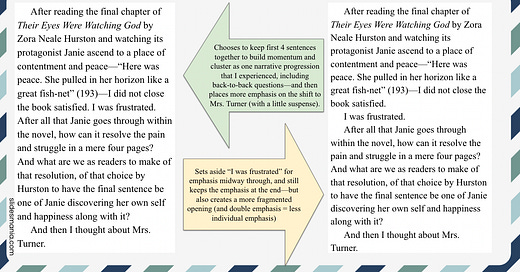

For example, we opened one class with a mini-lesson in which students discussed (and even debated) how to vary paragraph structure with the same block of text—and then reflected on the intentions behind different choices:

While many of these were quick mini-lessons or bellringers, it was a major shift in my own practice as I was taking the skills needed for the “challenge” and weaving them into our actual lesson in the classroom so that every student had a chance to experience and grow from them.

3. Better Supports = Increasing Challenge Access

To review, here was my own evolution with this particular sequence in the classroom:

Two years ago: toss a last-minute challenge at a few students unsuccessfully

Last year: invest in exemplars and tools to support students independently

This year: integrate the skills needed for the challenge into the classroom itself

Perhaps my biggest takeaway, then, and the major motivation for sharing my own evolution here: the number of students who were confidently pursuing this challenge in the classroom. It went from a handful of students to essentially the bar being raised for everyone in the room—and students bought in.

Creating this buy-in, I believe, is what I’ve struggled the most with in earlier experiences teaching. Too often “challenge” meant doing more and doing so independently, and even the students who did pursue it often had less-than-optimal experiences. (Making it that much harder to get them on board in future challenges, too.)

Compare that to this year, when [1] students had tools for the challenge not only provided but integrated into the classroom; [2] students emailed me individually to propose a topic idea and get individual support early in their brainstorming process; [3] we also created a peer workshop stage for them to share their progress and give feedback; and [4] students submitted a draft to me that they could fully revise after receiving my feedback. (Note: another related mistake I’ve made in the past is how I’ve at times disincentivized students from challenging themselves at times, usually unintentionally, by asking them to risk getting a worse grade if they stumble.)

This time? More tools and supports, but also a process from Day 1 that gave them a path to accessing the challenging task—a path that ultimately the vast majority of students went for.

Talk about a meaningful shift, right?

My Own Three-Part “Mistake” Takeaway

Going back to that drive home from daycare and my son’s question about what mistakes I made, I’ll frame this particular mistake in a three-fold manner:

I mistakenly thought of challenges as a mostly-independent pursuit

I mistakenly did not invest in the tools/supports needed for students to challenge themselves with

And as a result, I mistakenly limited access to the opportunity for students to challenge themselves

As I write this, I assure you that I’m also being generous to myself: we talk on The Broken Copier often about teachers being over-extended, and all of what I’ve reflected on here takes additional time and effort. This also was a three-year evolution for me in a supportive environment teaching the same learning sequence and making adjustments one year at a time—things that don’t exist in many teaching contexts.

But to return to my own learning here, I think the way I’ve shifted my mindset is more important than any specific choice or strategy.

Going forward, my hope is to think of what “the challenging path” would look like in future learning sequences and then consider how I can try to make this same evolution happen much more often: investing in better tools/supports and, ultimately, integrating the skills needed into the entire classroom.

And making our classroom better for everyone in it as a result.

A Few More Things!

Before signing off and returning back to the grading/feedback cycle a bit more this weekend, I wanted to share out an interview I did with

on reflection and why it’s so hard to center as a classroom teacher—I really enjoyed this conversation and feel like readers/listeners here might also find value in it!Furthermore, and in the spirit of today’s post, I also wanted to plug this reflection by

on the importance of “teaching the students you have,” as I think especially at this time of year it is important to not just stay present but invested in your own students and what they need from you as a teacher.Finally, I would be remiss not to mention two new books I’m really excited about: Alex Shevrin Venet’s Becoming an Everyday Changemaker: Healing and Justice at School (also: listen to her talk about it in this great conversation here with Cult of Pedagogy) as well as Tyler Rablin’s new release, Hacking Student Motivation. Both of these educators are people I have learned so much from, and I could not be more excited about both sharing their ideas and learnings in these books (one upcoming, one just released).

That’s all for this week—hope the weather is turning the right direction for you and the school year keeps churning in a good direction, too. —Marcus

Oh man…all the mistakes I’ve made…I think the entirety of my first two years of teaching was just one mistake after another.

This is such a great post! I have often dreamed about connecting my 5th grade classroom to a HS classroom so that I could collaborate around some incredible learning experiences. In this fantasy, both classrooms are close in proximity and while the HS students are reading Their Eyes Were Watching God, the 5th graders could be studying man versus nature and completing a complimentary project. I love the idea of taking a high-rigor project and differentiating it back to my 5th graders.

Thanks for the shoutout! I appreciate it.