Humble Teaching: a Story and a Stage

Some thoughts on why humility is both incredibly hard but also incredibly important as a teacher—with a quick story to begin.

In my second year of teaching, I was interrupted mid-lesson by that student—the one always raising their hand to ask a question with the most sincere expression of urgency that you can imagine, and this time with their arm stretched beyond its socket.

“Mr. Luther,” they said, giving the classic eyebrow-raise-head-nod combination to underscore how important it was. “Come over here.”

I shook my head, determined to continue whatever point I was trying to make to the whole class that surely felt important at the time. This first classroom of mine even had a small stage at the front of it (it had formerly been the drama teacher’s room), allowing me to impart my wisdom from my seated perch to the onlooking students below.

“Mr. Luther!” they said one more time, now waving their arm frantically.

“If it’s that important, _______,” I said, visibly sighing as I had already conceded momentum at that point, “you can write a note and I’ll come grab it in a second.”

Somehow, this worked—they furiously started scribbling and I thankfully went back to my lesson. Problem solved.

Until they had finished their note, and once again started trying to get my attention—this time while waving the paper aggressively in the air.

Another sigh.

I stepped off the small stage and walked over to their desk and opened the note, and read the following words:

Mr. Luther, your pants ripped and when you’re sitting at the front of the room everyone can see. Thought you would want to know.

Another sigh.

I’ve been thinking about humility lately

A week ago I posted briefly about this topic, noting that leading with humility is especially challenging when that leadership is constantly visible, with actions of humility having to reconcile with the fact that those actions are on public display at all times.

Then, of course, as almost everything on The Broken Copier tends to circle back to, this made me think a lot about teaching.

Let’s start here: humility is hard as a teacher—and not only when you have a rip in your pants and are unwilling to get feedback from a student trying to save you from further embarrassment.

I think it is really difficult for someone who has not been at the front of a classroom to empathize with not only the sheer volume of decisions a teacher has to make in a given day but also with how open those decisions are to scrutiny—most immediately by the students watching your every move from their desks. Really, the entire construct of traditional education rests on the presumption that the person in the front of the room is the expert—the teacher knows some stuff, the students learn that stuff from them.

Rinse and repeat for over a century.

That creates incredible pressure to teachers to project confidence in the role, not only presenting mastery of the content one is teaching but the pedagogical manner in which it is taught. Syllabi are sacred document, henceforth, and what the teacher says, goes.

Even if it would be really helpful there a gaping tear in one’s pants, metaphorically speaking.

But quite honestly, the work of teaching is a minefield of torn pants, right? Knowledge isn’t fixed—what we know about the world evolves! And if part our goal is to prepare students to succeed beyond our classroom, well what happens within our classroom certainly must evolve, too. A commitment to being the best teacher one can be ultimately is a commitment to recognizing how to become a little better teacher each day.

And all that requires humility.

For example, take the case of grading

In our most recent episode of The Broken Copier, Jim and I explored some of the current perspectives around grading as well as criticism of them—but for both of us, looking at the clear fault lines as well as a lack of obvious, comprehensive solutions going forward, this was precisely where educators needed to make sure humility was front-and-center.

Jim made the following observation at one point (and I’ve included the video clip below of that segment of the conversation):

People are very convicted one way or the other, Jim noted, and think that such and such is the best practice—and maybe it is—but I don’t know. For me, I think there’s a lot more room for humility and actually slowing down and talking some of this stuff through…

Jim’s 100% right! In the face of contradiction and a changing landscape, this isn’t the time to say “I know what’s right” as much as to say “let me pause and learn.”

However, as I pointed out in the conversation, an authentic pedagogical humility is all well and good but teachers are assigning grades right now. (I literally just closed out a tab of updating my grade book over the weekend before beginning this post!)

And this is where the importance of humility collides directly with the difficulty of humility: how can the expert at the front of the room—the one responsible for assigning grades that are incredibly consequential in the current schema for students—express humility about a system of grading?

This is especially true for the most difficult of topics in education: how to assess knowledge; which standards to prioritize; how to reconcile with technology advances; how to balance supporting students with challenging students. How to do what’s best for the individual student while also doing what’s best for the entire room.

All of these are incredibly challenging with no clear right answer, and therefore all require a humility that is undermined by the very fact that teachers are in front of rooms making choices and being accountable to those choices on all of the above topics and a thousand others daily.

Therein lies the paradox. So what do we do?

Back to that stage at the front of my first classroom

One thing I know for certain at this point of my career: as a brand-new teacher, having a stage in the middle of your room is a very humbling thing.

The number of stumbles over my three years teaching in that classroom were memorable for all who witnessed them, not to mention how they were probably overshadowed by the myriad more near stumbles and all the laughter that ensued within our classroom amidst all of Mr. Luther’s collapses.

Talk about humility, right?

But therein lies the answer, I think: talk about humility.

With your students.

Here’s what I mean by this in my current classroom: I try to be incredibly transparent about my own power (“the stage”) in the classroom as a teacher, including being open about the choices I get to make as far as what we do. I explain my thought process and reasoning but also my concerns, at times, as well as my mistakes (“the stage!” again)—and then, especially in the latter half of the year, I try to get genuine input from students about what they would do, if they were making the decision

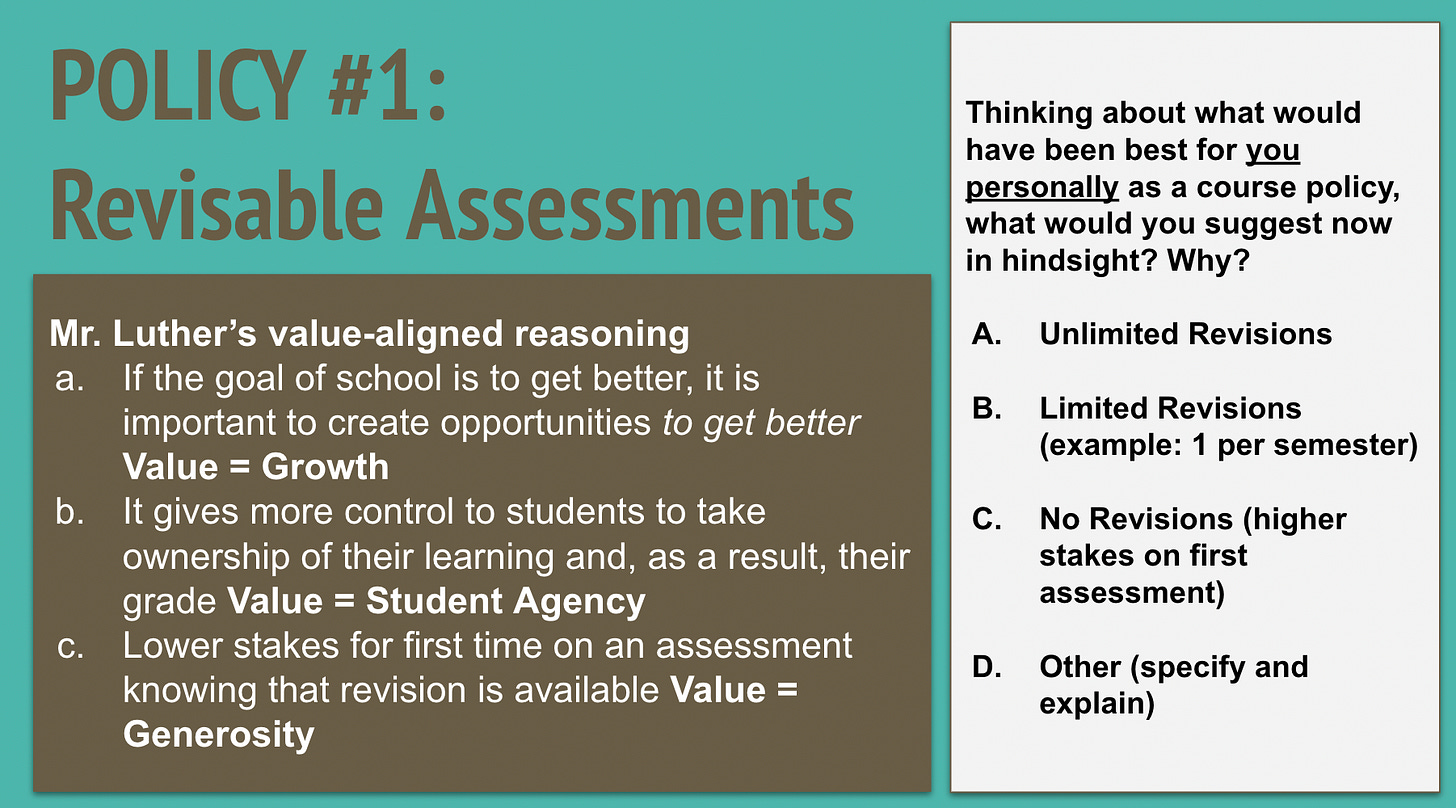

Here’s an example of a “policy discussion” we had last year as a classroom that informed my choice of policy going into this year:

That’s the recipe for me right now as far as humility:

Try to be open about what I believe is right and what values drive that belief

Try to also be transparent about my own locus of control: acknowledging the decisions I have control over versus those I cannot

Try to bring stakeholder voices into these discussions in a genuine way, and if necessary to advocate for what students say is best for them

Humility, after all, isn’t just about acknowledging when you make a typo on a Google Slide presentation (which happens daily for me) or when you realize in the middle of the day that you have a rip down the inner seam of your pants (thankfully this taught me to always have back-up teaching clothes on the premises!).

Rather, humility is about being open about one’s own power as well as limitations as a teacher, and inviting your students into the process as much as you can to make sure their voices are heard and affirmed—and then acknowledging how very rarely is there a best choice that is 100% right for everyone, and that the work comes just as much after that choice is made to figure out how to get a little better the next day.

At least I think that’s what humility is, for me, in this moment, as a teacher.

I think.

On a separate note, thanks to all who continue to support The Broken Copier by reading and listening! (Also: there’s really nothing in education more humbling than the realization that the copying machine is broken, right?) For Jim and I, watching this network continue to grow has been a true joy—and never hesitate to let us know if you’d like us to focus on a certain topic, share a resource we’ve mentioned, or have feedback about how we can do better!

I’ve also started writing for a separate website, MovingWriters.org, so you’ll occasionally find me over there—such as this past week, with my piece on having students annotate their own writing before submitting.

If you haven’t subscribed to The Broken Copier, feel free to join our community here—subscribe below if you’d like our podcasts and writings to go directly to your email:

And finally, congratulations for reaching March 2023, and good luck to all of those in education who are about to endure the gauntlet of state testing, next-year forecasting, and end-of-year shenanigans around college applications, scholarships, and graduation. The home stretch is a true thing in this education world, isn’t it?

Best from us at The Broken Copier and take care!

—Marcus

This resonates on multiple levels:

1- Early humiliation. In 1993, in my first teaching assignment, Darnell raised his hand after one of my “speeches” to ask, “Miss, did you know your nose flares out when you yell?” Ooof. Next year I read Haim Ginott’s Teacher and Child and got better.

2- Slow gathering of Velveteen Rabbit wisdom: learning to admit mistakes, make amends, acknowledge the limits of my knowledge, and seek input.

3- Openness to a more profound power sharing. I’ve begun turning over some decisions to the will of the class after discussion and inquiry. Especially regarding how we use time for upcoming themes and topics, how we approach a topic, etc.

I’m much less cocksure about pedagogical practices -- 31 years in education, 9 years in PD, and an Ed.D. have made me less sure and more aware of a huge body of contradictory research and the limits of what we really know. The current pronouncements about ungrading being the only ethical stance make me tired. They shut down discussion. They close out all those who are pragmatically trying to figure out tomorrow. Those education thought leaders whose tweets are framed as “the only way” do more harm than good. Their harsh delineations between good and bad are often born of a lack of recent experiences in the trenches or a privileged position within a privileged educational system.

Thank you for your thoughtful and humble writing on the subject. Now I’m off to retract an assignment in the syllabus (which I borrowed from a professor), since it’s untenable for my undergrad students. We’re going to figure out the adaptation together as a class with me as the guide.