Maybe Go Back and Try...What Didn't Work?

a reflection on trying two strategies this year that I had previously written off

When reflecting back on our pedagogical journeys as educators, I think a lot of us initially consider a linear path: I used to think and do this, now I think and do this, etc. We try things and we make mistakes and we learn and do differently in an attempt to do better.

If only it were that simple.

Not to fall into the “time is a flat circle” True Detective meme (also: credit Nietzsche), but I think most of us recognize that more broadly education is far more often cyclical than it is linear when it comes to progress—and while it may take some humility to admit it, I believe we too fall into that cyclical pattern of growth ourselves as educators.

Revised, more honest version, then?

We try things and we make (many) mistakes. We learn (sometimes) and do do differently (sometimes) in an attempt to do better (we think)—and then sometimes we go back and try those things again to see if they might actually work.

Which I don’t think is necessarily a bad thing.

I wrote this summer about the importance of humility in our work, and for me I’ve tried to put that mindset into practice this year by reconsidering some previously-discarded strategies in the classroom.

So that’s what I wanted to do in this post today: share and reflect on two strategies I’m trying this year that I had previously shifted away from.

(Spoiler: so far, they’re going pretty well!)

⓵ The Reading Accountability Quiz

Why I had previously moved away from it: Several reasons! First and foremost, I recognize that homework itself is inequitable, but in trying to navigate my AP Literature course and prepare students for the end-of-year exam, I cannot avoid the fact that at least some of the reading has to take place outside of class. In previous years, though? I leaned away from any sort of accountability for that reading in terms of “accountability quizzes,” as these felt like adding fuel to the inequity that already existed in the homework reading. Additionally, amidst frequent student absences, navigating who had to take which quiz over what chapter became very overwhelming, very quickly. So I basically scrapped the concept of these quizzes entirely and leaned on our bigger assessments (essay, seminar, etc.) as the accountability for the reading.

Why I decided returned to it this year: As I reflected going into the year, one of my priorities right now is to try placing more emphasis on Level 1 Questioning and content knowledge overall as an ELA teacher—which means, in practice, adding weight to the actual reading of our novels in AP Literature. I also had to acknowledge a very real quandary in my classroom in recent years: students were aware that there weren’t many grade repercussions for missing readings semi-frequently, and given that there were repercussions for their other courses, our assigned readings were understandably getting sidelined. (This also became a bigger issue when students walked into end-of-unit assessments like a literary analysis essay without a strong enough understanding of the novel itself.)

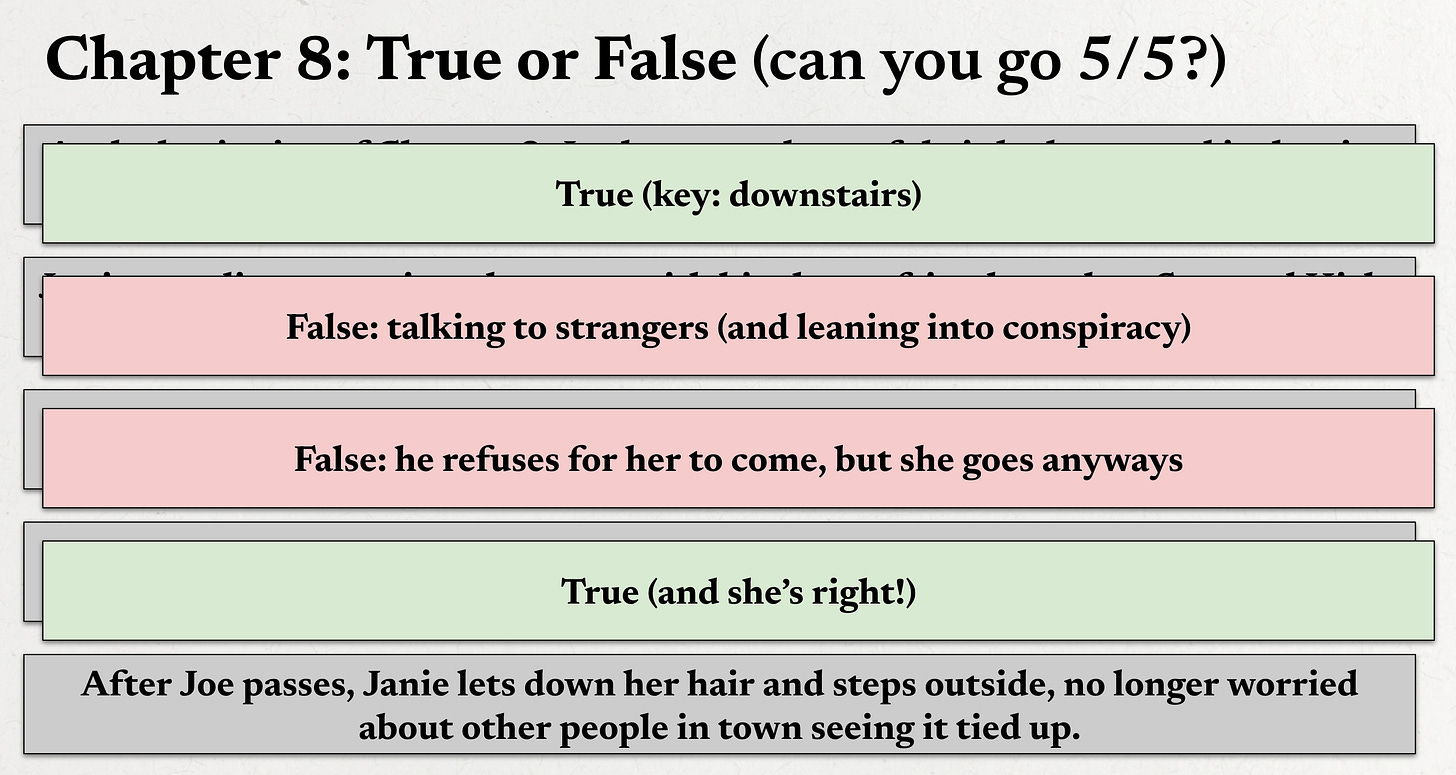

What it looks like in the classroom: After any assigned reading, we begin class with a review of the reading via true/false questions as a self-check (and also an entry into the discussion that day for those who were absent or had not done the reading yet). As you can see in the image to begin this section, this is a low-stakes way of checking for understanding—and also a convenient way for me to compile true/false questions to use at the halfway point and end of the novel. At those two points in the unit, students are given a brief quiz over entirely composed of true/false questions to hold them accountable to what has been assigned, particularly outside of class.

Why I think it is working: Rather than trying to have a formal assessment for each assigned reading, I chose to use two longer quizzes that together covered the entirety of the novel (the first for Chapters 1-10; the second for 11-20); moreover, in trying to combat the equity issue of assigning outside-of-class readings, I stretched the unit out an additional week so we could cover more of the novel in class. Adding in the in-class reviews embedded into the unit already, I have been surprised to see that many students actually are now looking forward to these quizzes with confidence as a way of showing what they know and the work they’ve done with the book overall—and this has been a “rising tide” for other aspects of the unit, such as diving into their essays and our fishbowl seminar discussions over the book.

⓶ The Teacher Lecture

Why I had previously moved away from this: When I stepped into the classroom in 2012, not only was I already very familiar with the trope of the “sage on the stage” old-school style of teaching, but I also literally had a stage in my classroom. (A feature of inheriting a former drama room to begin my ELA career in.) In my mind, the worst thing you could do as a teacher is stand at the front and talk at length about the reading at students—much better, instead, to work to build a collaborative, authentic community in the classroom for students to discuss their own interpretations with each other. Right?

Why I decided returned to it this year: I received a very thoughtful piece of feedback near the end of our first unit from a student who pointed out that a) they understood and valued the amount of collaboration in our classroom but b) they sometimes felt adrift in relying so much on their peers for interpreting, and wondered if there could be a bit more teacher-driven learning. Yes, this was just a single point of feedback from one student—but rather than dismiss it as an outlier, I used it as a way to reflect on my own priorities pedagogically: was there a downside in completely avoiding any type of formal lecturing as an ELA teacher? I decided to find out by trying out a strategy I really hadn’t ever leaned into as a teacher in 13 years of teaching.

What it looks like in the classroom: After select readings in our second unit with Their Eyes Were Watching God, I prepare a brief formal lecture over what I believe is essential to notice and consider for that section of the novel. I guide students through several key pages and quotes from the reading collectively as a class while offering my own interpretation of their significance, and as I do this I ask students to take notes as they see fit in their spiral for that 5-10 minute stretch while I’m at the front of the room. This is then followed by students debriefing their notes with partners before asking me about any clarifying questions they might have.

Why I think it is working: Similar to the first “return” I shared above with the reading accountability quizzes, I believe it is important that these lectures are neither frequent nor lengthy—only a handful of times over the past month, usually only around five minutes. By adding in the peer debrief, too, I think it makes them “stickier” as far as retention—and I also prepare my formal notes to include in the lesson slide deck as speaker notes in case any absent student needs to access them. Most importantly, though, what I’m noticing as a result of this addition is that far more students are moving through the novel with confidence now that they have some clear, essential understandings under their belt. What I’m realizing, too, is that by giving them a bit more direct instruction via lecture, I might actually be opening the door to students being more confident later on in forming their own interpretations, as in previous years students who felt adrift without support in the earlier stages of the novel may have shut down.

So Non-Linear Progress Might Be Okay?

If you’re reading this and thinking that I am now crowdfunding for a new stage to lecture from in my classroom and ordering stacks of Scantrons for future quizzes, let me assure you that my pedagogy very much remains in a place that prioritize collaboration and resists too much emphasis on Level 1 questioning.

In other words, I’m still me.

Yet as you have read in this post, I have found some success this year in setting my pedagogical ego aside for a bit and dipping back into those past “mistakes” that I had previously written off.

Does this mean the answer going forward is to just do a little bit of everything pedagogically? I don’t necessarily think it’s that simple, as there are some things that do far more harm than good—plus, there’s only so much time, so doing one thing often means not doing another.

Still, what I’m realizing, even as I type out this post, is that having the humility to be open-minded towards viewpoints and pedagogies different than my own is even more important at this stage in my career—and the advantages are felt more, too, as I feel like my experience allows me to try “old mistakes” in a way that limits their downsides and makes the most of them in the classroom in a way I previously was unable to.

So much is said about looking forward and trying new things these days (mostly well-intentioned); however, if there’s been any lesson from my classroom this year, it just might be the importance of remaining humble and taking a second look at strategies I previously had discarded.

You never know what you might find, right?

Several Links Before Signing Off!

As noted in last week’s post, like many educators both Jim and myself have made our way over to Bluesky and are planning on spending much more time sharing resources and exchanging ideas there. Feel free to follow us there, as it feels like an exceptional place for Broken Copier folks, based on what we’re seeing so far!

I also had a chance several months back to record a conversation on embedding self-reflection for independent work while also leaning into collaborative learning in the classroom on the Vrain Waves podcast—and the episode just came out this past week! I really enjoyed this conversation and encourage you to give it a listen, if you want.

Many of us have read many reflections on the election and how it intersects with our experience as educators over the last week—and the one that spoke most immediately and resonantly to me was written by

: “What Now? Don’t do the job. Do the work.” It has lived in my head persistently and purposefully ever since reading it, and perhaps some of you might find it meaningful, too, as we chart a path forward.Finally, our Fall Book Study of Alex Shevrin Venet’s Becoming an Everyday Changemaker continues tomorrow with a post from

on Chapter 6—and you can access his Substack newsletter here to dive into that conversation tomorrow, if you’d like!

AI Disclosure note: the article cover image is AI-generated using Canva with the prompt, “recycled pile of papers and ideas in the sunlight on a classroom desk” (no other AI was used in the writing or revision of this article)

I appreciated this reflection. Both the specifics of your ideas and also the notion that progress isn't linear, that a teacher can move back and forth between differing approaches and remain a good teacher all along the way.

Thank you for these reflections! I often feel like the hold out for student accountability with these brief reading quizzes. However, it promotes a culture of valuing the diligence of the students who are doing the work by showing that being successful sometimes take an investment in the effort and not just riding the coat-tails of what others are contributing to class.