My 2023 Takeaway: The Value of a More-Responsive Classroom

a reflection on why and how a "more-responsive" classroom matters

The other day mid-lesson I found myself in the position that all of us teachers absolutely abhor: students were disengaging.

It was a problem entirely of my making, too.

(Well, I’ll also add, perhaps a little a result of the collective exhaustion of students and teachers alike just about to collapse into Winter Break, but for simplicity’s sake I’ll shoulder 100% of the blame for this anecdote.)

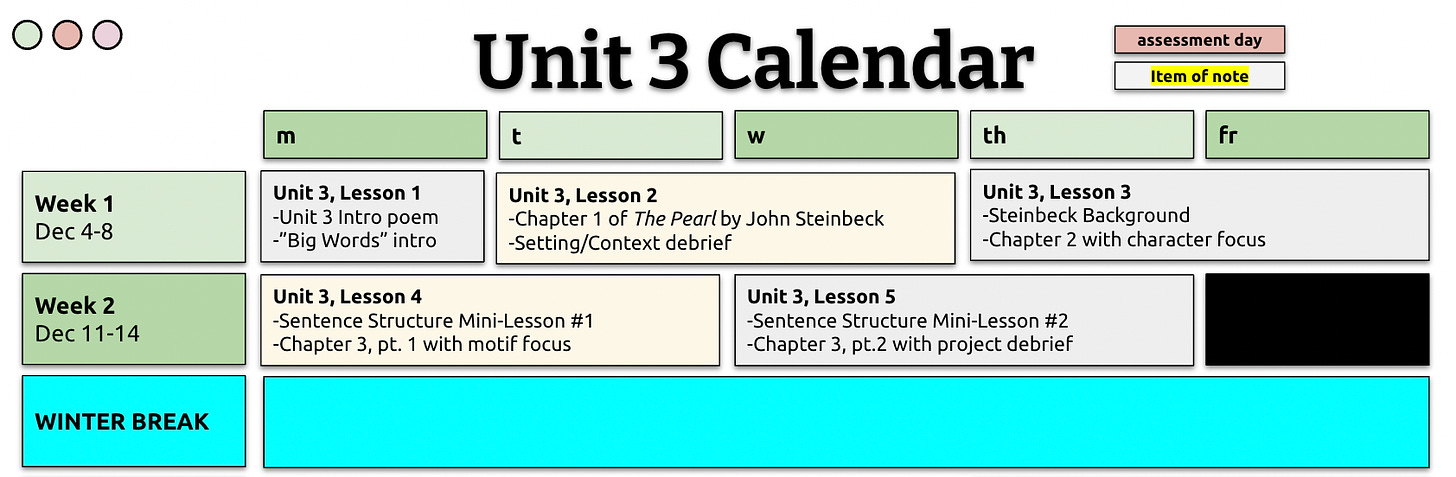

The reading I had planned to cover that lesson was taking too long, which meant that we were moving through it without much classroom conversation in order to stay “on pace” with the calendar I had drawn up before Winter Break:

To make it worse, there some glitches with the technology and the audiobook was not working—so instead I was reading aloud, trying to simultaneously breathe life into a reading that was falling flat while also trying to encourage engagement as I moved around the room, haphazardly weaving through desks to encourage students to stay locked in while staying “in character” as I read aloud from the third chapter of The Pearl.

Needless to say, this was not working at all.

So—I found a reasonable stopping point, had everyone to close their books, and asked them a question that had popped into my head while reading: is it better in life to be too hopeful or too cynical?

The next 20 minutes or so built off of this: every student answered individually aloud in front of class while I kept an informal count of the results, then groups dove into conversation about the reasoning behind their answers—followed by more whole-class conversation, debriefing and escalating and, as a result, authentically breathing some life into a room that had been almost entirely deflated.

Was this what I had intended with this lesson? Of course not.

But it was undeniably a better outcome for our classroom than if I had stuck to the plan.

“A plan is nice.”

My first book of Winter Break was A Swim in a Pond in the Rain by George Saunders, a collection of Russian short stories that he teaches in his college course along with his own thinking about them from a storytelling perspective—and of course, as I tend to do probably too often, throughout the book I found myself falling into my own analogy as a reader: a classroom is a story, in my mind, so good storytelling, according to George Saunders, must be good teaching.

With this in mind, I arrived at this moment in the advice that Saunders lays out for storytellers: “If we set out to do a thing, and then we (merely) do it, everyone is bummed out.”

He uses the example of how empty a conversation with another person would be if you relied fully on a pre-planned set of index cards to adhere to in your dialogue. “A plan is nice,” Saunders acknowledges, “With a plan we get to stop thinking. We can just execute. But a conversation doesn’t work that way, and neither does a work of art.”

Neither does a classroom.

This is when I had to pause my own Winter Break reading plans for a bit, close that exceptional book by Saunders (seriously, if you’re an ELA teacher, couldn’t recommend it more!), and begin typing a reflection about that problem-of-my-making in the classroom with students disengaging from what I had planned and me, realizing this, doing what I could to pivot the classroom to a different type of a space to meet our classroom community where it needed to be met.

This isn’t just about a single lesson, either.

Earlier in the book, Saunders writes, “A story is an organic whole, and when we say a story is good, we’re saying that it responds alertly to itself.”

Yes, that applies to how a teacher moves through an individual lesson, but the real takeaway for me—not just from this book, but from the year 2023 as a whole—is that the classroom needs to be a responsive entity as much as possible, in as many ways as possible.

Let me offer another circumstance that goes beyond any particular lesson:

For AP Literature, our final instructional unit of the first semester is when we dive in headfirst to poetry—perhaps my favorite instructional unit of the entire course. However, students often step into this poetry unit with a fair amount of resistance, holding many preconceived fixed (and negative!) mindsets around poetry itself.

The opening lessons, then, offer quite a bit of hand-holding, walking students through a process to help them build perspective and also confidence in navigating various poems. The goal? A consistent, step-by-step process that we go through again and again for the first several lessons of the unit—and an admittedly teacher-driven process I also had already planned out in-detail, leaning on what had worked in previous years.

The problem? In our latest check-in survey, these AP Literature students had expressed A) how much they enjoyed learning from each other’s ideas in group work and B) how a change of pace was needed in the “grind” of the first semester.

So there I was looking at an already-planned-out two week stretch of lessons that, despite being well-designed and successful in past years, did not respond to what students in the classroom said they needed.

“When we say a story is good, we’re saying that it responds alertly to itself.”

Continuing the story-to-classroom analogy, does “responding alertly” mean that I scrapped everything and started from scratch? Nope—but I did make two intentional shifts to the sequence I had planned out:

For the second lesson, I added in an interactive “most important words” charting activity that got students out of their seats exchanging ideas with classmates and then in groups narrowing and voting.

For the third lesson, I dropped the “teacher-driven” aspect entirely and let students explore the poem on their own first and before moving into “super-groups” for a competition of who could make the strongest analytical “slide” in a shared classroom slide deck (see one sample below)—all with Fortnite music blasting in the background.

Responsiveness doesn’t just take place within a single lesson—in fact, the more meaningful responsiveness has to be broader, I’d argue, if it is going to an authentic value of your pedagogy.

5 ingredients (I think) for a more-responsive classroom:

Responsiveness isn’t just about intention, either, and I think it’s important to be clear-eyed about what it takes for teachers to be more responsive in their own classrooms—both in terms of mindsets and skills.

After some reflection, I came up with “5 ingredients” that make a more-responsive classroom possible:

Humility. A major part of being responsive is stepping into the classroom each day acknowledging that no matter how much you prepared and how experienced you are, you do not on your own know what your students need. You have an important vantage point as the teacher in the classroom—but that important vantage point is also inherently a limited one.

Student feedback. The solution to our own “inherently limited vantage points” as teachers? Building a classroom community in which students are not just asked for feedback but empowered to believe it matters. I won’t go into detail here since we’ve shared a lot on this topic this past year (for example, here and here and here and here)—but it goes without saying, without student feedback your classroom cannot be responsive to your students.

Pedagogical tools. This is where it gets tricker: your students asked for something to meet their needs as a learner—do you have the tools and strategies as a teacher to respond? Give yourself grace here first, especially as an early-career teacher, as teaching tools aren’t developed in a day. But I also believe this should drive your own willingness to keep learning and exploring as a teacher—and yes, experimenting in the classroom!—to make sure your “pedagogical tool belt” continues to grow and, consequently, allows you to be more responsive to the needs of your classroom.

Content mastery. Pedagogical tools only take you so far when your mastery of your content is limited. This is especially true when taking a step back beyond a specific lesson and considering how your scope-and-sequence more broadly can respond to your particular classroom. Part of my ability to make that mid-lesson pivot with The Pearl and the two-week lesson shift with our poetry unit was very much my understanding of the skills and understandings students needed and my belief in the different ways we could arrive there. That isn’t a “Year One” flexibility, either—a reminder, I think, that we shouldn’t allow a focus on pedagogy to overshadow the importance of knowing one’s own content with as much confidence and capacity as we can.

Context. This final ingredient? Probably the most important and, unfortunately, the one that we have the least control over as a teacher. Are you planning for 1-2 classes or 3-4 classes? Do you have a mandated curriculum with required pacing across your content area? Do you have administrators (like I do!) who foster creativity and experimentation as a teacher—or is it frowned upon in your building? Do you have the energy based on how outside-of-school life is going for you to invest in some new ideas—or are you just in the season of your life where you have to do your best with what you have? All these questions matter a great deal and all are very much beyond your locus of control. That’s important to note, too.

The final ingredient? Generosity towards yourself.

Let’s return briefly to that two-week stretch of poetry before Winter Break, where I shifted two lesson designs to respond to feedback from my students.

The other lessons in that two-week stretch? Largely left untouched.

And I think that’s okay.

In adjusting that two-week sequence, I tried to be responsive to student needs while also keeping in mind my own capacity as far as time and energy.

To circle back to my “learning” from earlier in this post: the classroom needs to be a responsive entity as much as possible, in as many ways as possible.

Even though this twelfth year in the classroom has been incredibly positive for me, I absolutely collapsed into Winter Break, even after a really positive final week of lessons. As teachers, the past few years have been ridiculously taxing, and I’m sure reading this post about the importance of “being responsive”—i.e. pivoting mid-lesson for a class lacking energy, adjusting plans you had already made, etc.—just sounds like more.

More that you’re asked to do as a teacher, or more that you want to do but don’t feel capable of doing. (A reminder too that, at least in education, the synonym of “more” is “too much”)

So when I write about being “responsive” in the classroom as my priority going forward into 2024, I realize that it can sound like yet another more for already-burdened teachers—especially when considering the “ingredients” I listed that include variables often outside of a teacher’s control.

That is why I am advocating for a “more-responsive” classroom, not an “entirely-responsive” one. It is an intention, an admittedly aspirational one at that, not any fixed destination any of us will ever arrive at.

So let’s end here: How responsive is your classroom? And what can you do to make it more responsive to your students’ voices and needs going forward?

I think those two questions offer a well-enough starting point for now.

Goodbye 2023, Hello 2024

And that’s a wrap, folks—at least for 2023!

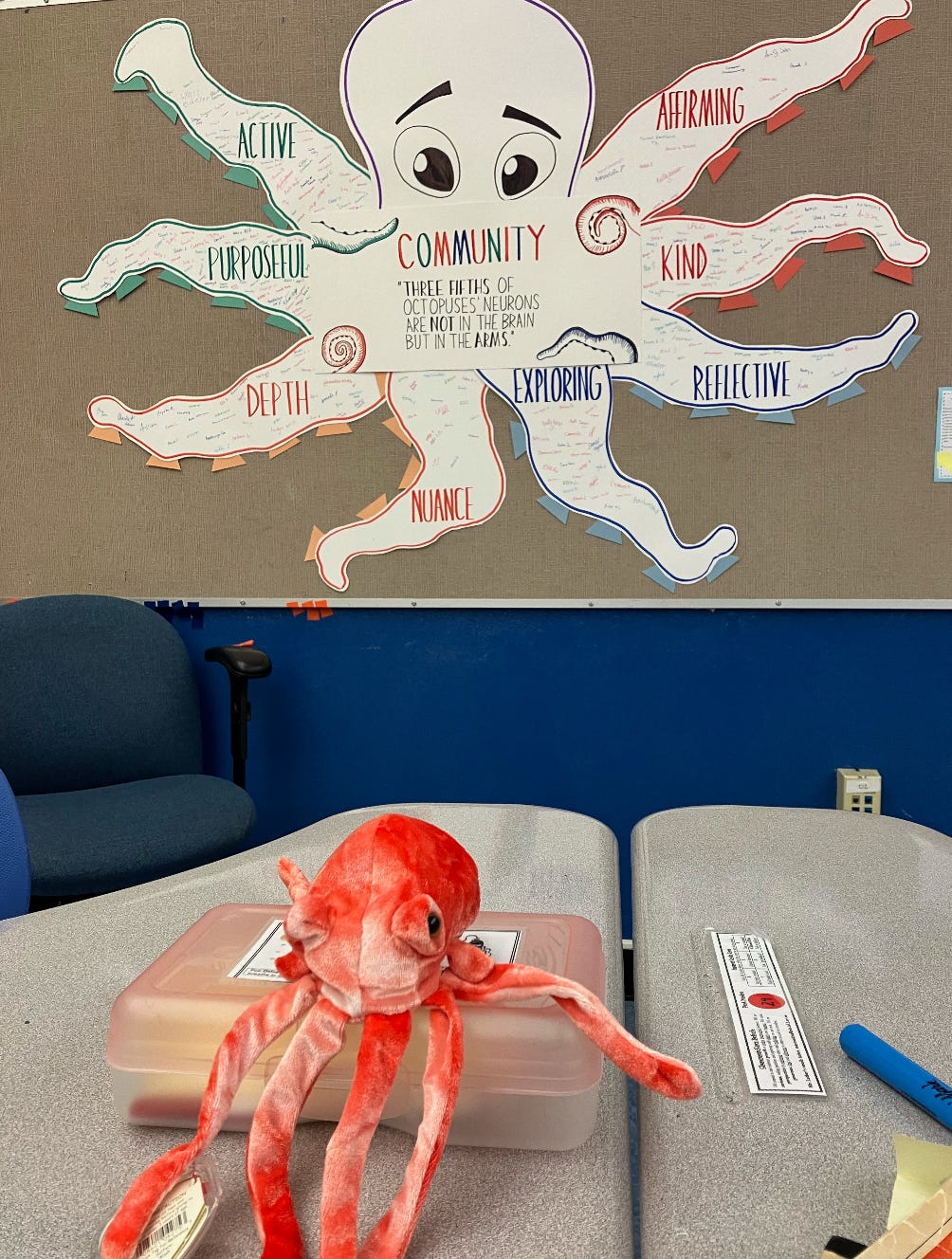

On a personal note, this calendar year was without question of my favorites as a teacher—with one of the final classroom memories being a group of seniors I taught last year “gag gifting” me the arch-nemesis of our classroom octopus theme: a squid.

Talk about responsiveness, right?

I’m also incredibly grateful for everyone we have been able to connect with via The Broken Copier—the kind notes and messages, the thoughtful questions and conversations, and especially the examples of ideas discussed on here showing up in classrooms all over the country (and even in other countries!) have all been the exact fuel we need to keep this platform and community going.

So: thank you. For continuing to engage with and share out The Broken Copier posts and podcasts, of course, but more importantly for being as invested as you are in pushing for better classrooms everywhere that are more supportive and purposeful for teachers and, consequently, the students we all serve.

And here’s to a more-responsive 2024!

—Marcus

The classroom is such a dynamic environment, that it is foolish to NOT be responsive. So often, teachers try and use technical solutions to “fix” problems in their classrooms (e.g.: disengagement, disruption, etc.). There are no quick fixes in the classroom because there are 20-30 other human beings in the same learning environment. I love how you discuss shifting your mindset. I find that shifts in my mindset, building relationships, continual experimentation, reflection and iteration seem to be the best (and most humane) way to run a classroom.

Love this post. And I would add another ingredient that I believe is a bit of a roll-up of several you mention: relationships. It's where I find myself going when I hear sky-is-falling concerns about AI replacing teachers. AI can be responsive to a point -- but it lacks the ability to create real connections and relationships (don't let the movie "Her" convince you otherwise).

It's why I said a few weeks ago..."Still, I hope we never ask a bot to comfort a sad kid." Being responsive on the level you're discussing requires the ingredients you mention -- and it requires that you've invested in the number one tool (pedagogical, socio-emotional, human) for your tool belt: growing connections and relationships.

Have a great winter break.

https://beccakatz.substack.com?utm_source=navbar&utm_medium=web&r=1ji450