The Classroom As It Is Is Enough

Or at least it can be—if we choose to make it so.

Over Winter Break I was finally able to open up the majestic book that is Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr—seriously, it is one of the five best books I’ve ever encountered!—and I arrived at a point late in the book in which I had to simply set the book down and go for a stroll.

Without spoiling anything plot-wise, one of the main characters comes across a long-forgotten, nearly-lost story from centuries before—an already-translated tale that a group of children end up editing with their own more-accurate translations at the very end.

In this centuries-old story—one that serves as a through-line for the myriad characters and timelines of Cloud Cuckoo Land—the protagonist Aethon has to choose between eternal happiness and freedom from desire or a return to his own world, one that he had adventured and endured incredible hardship to escape.

He ultimately, and somewhat shockingly, chooses to return to the imperfect, desire-filled world, with the children translating their own explanation of his reasoning: “the world as it is is enough.”

That was the moment I had to close the book for awhile and take a long walk.

And think about the classroom.

when we center affirmation

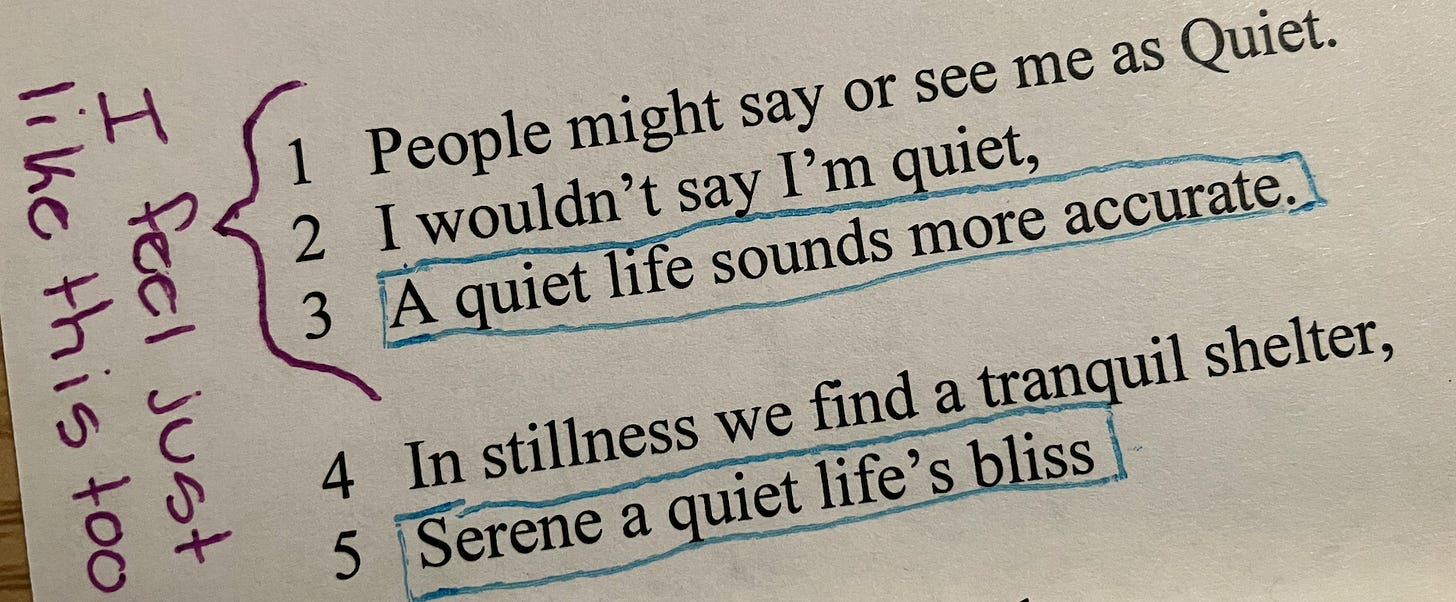

Last week, students took part in what has quickly become an annual rite of passage in our AP Literature class: they left the classroom and walked down the long hallway to our school library with colored pens in hand, stepping into a space in which over eighty narrative poems were spread out on tables and shelves and counters stretching from one end of the library to the other.

Then, in complete silence, they went to work for the next thirty minutes: reading each poem they came across and adding a thoughtful piece of affirming feedback to the narrative poems of their classmates.

Poem after poem, affirming feedback after affirming feedback.

All in complete, wonderful silence.

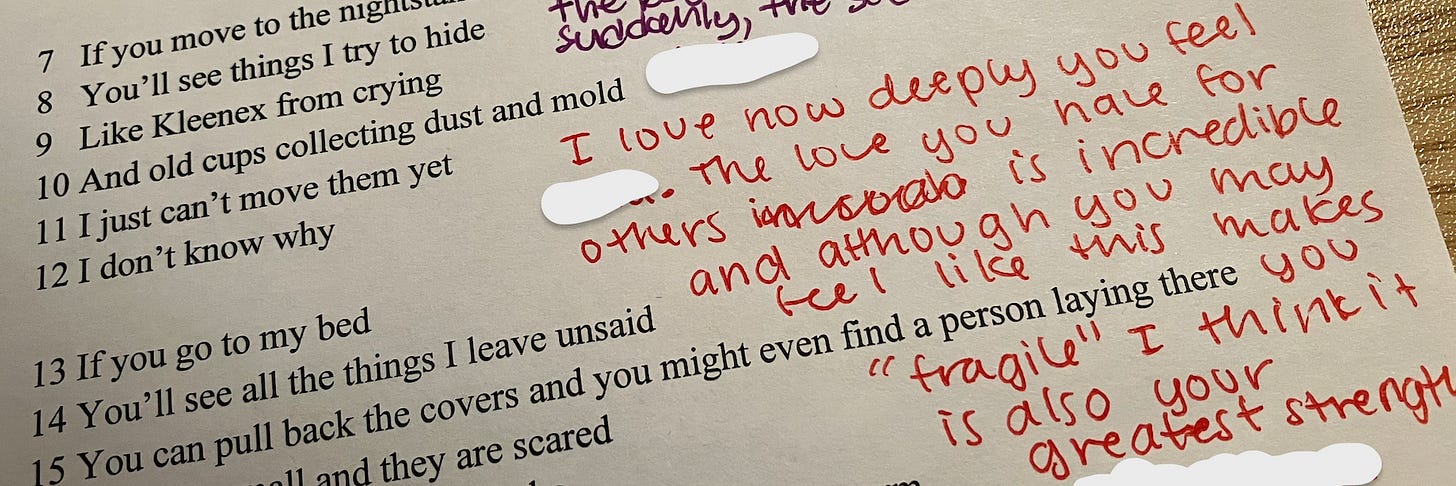

To give a quick sampling of the type of things they added to their classmates’ poems:

“This is so facts…I feel you explained feelings that I could never begin to explain for myself and that’s amazing.”

“You found a way to ‘pull’ inescapable thoughts from your mind; creating a safe place for others.”

“I love the confidence at the end, I struggle with this very thing and it’s very inspiring to see you write about it.”

“The love you have for others is incredible and although you may feel like this makes you ‘fragile’ I think it is also your greatest strength”

I know I’ve written about this activity before, multiple times, but yet again I find myself not being able to do anything else but share out what incredible things students can do when you give them a chance not only to share their words through poetry, but to then encounter each other’s words and speak back to them.

I mean, just take a look:

the classroom as it is can be enough

Returning to Cloud Cuckoo Land briefly, the character who comes across this translation near the end of the book is very much full of cynicism at that point—not just about their own life, but about the world overall.

“He’d convinced himself that every human he saw was a parasite,” the book observes, “captive to the dictates of consumption.”

As teachers, I know that cynicism can feel like our only alternative these days: to look at our world within our classrooms and beyond our classrooms and feel overwhelmed by what is being asked of us as well as our students. (Looking ahead, 2024 does not promise less-turbulent waters, either.)

Yet this page of the book pulled every part of me as a teacher into it—not only my cynicism but also my anxiety and my values and my perhaps-foolish hope for what I desperately want for my classroom and every classroom.

“…the truth is infinitely more complicated,” this main character realizes on this page, “that we are all beautiful even as we are all part of the problem, and that to be part of the problem is to be human.”

To be part of the problem is to be a teacher, too, even amidst the myriad, beautiful possibilities that we encounter each day.

“this is something everyone should experience”

Returning to the classroom after their gallery walk of narrative poems from classmates in the library, students were asked to reflect on what the experience was like—first in writing, and then in groups.

Some things they said:

“I loved this activity because it was a very cool window into my peer’s lives.”

“I liked that other people share my same thoughts.”

“I didn’t read any poems that were about the same thing.”

“Giving feedback is also vulnerable and I don’t get like that with people, almost ever.”

“Seeing my peers writing really lit a fire under me.”

“I felt like this is something everyone should experience.”

We then took it a step further this week when poems were returned, now filled with feedback from their peers. Along with celebrating the poems themselves—students vote on their favorite titles to award “crown signings” in our room, for instance—we also celebrated the best examples of affirmative feedback.

The students who gave the most affirming feedback to their classmates throughout the activity? One at a time, celebrated by the entire room.

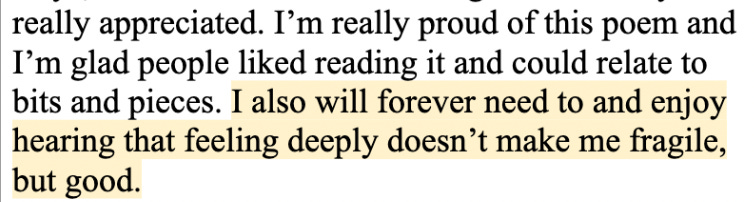

From there, students recorded their own thoughts on their year-long reflection trackers for writing.

Recall that feedback from earlier, when one student wrote to another, although you may feel like this makes you ‘fragile’ I think it is also your greatest strength.

Looking through their reflections the other evening, I came across this:

Affirming feedback from one student onto a narrative poem of another that then was recaptured in silent reflection as a takeaway from the entire activity.

That then left me once again needing to close what I was reading on my laptop and take another pause, this time overwhelmed by words of students.

And—filled with gratitude and hope—to think even more about the classroom and what it can be.

our classroom is what we center within it

In our most recent podcast, Jim and I responded to a listener question about not just engagement in the classroom, but a deeper sense of disillusionment with the enterprise of education overall. One point we both agreed on, then, was how too often we shape our classrooms baed on future-oriented, “this-is-what-you-need-for-college” justifications.

Speaking plainly: those aren’t enough. They weren’t before, and they certainly aren’t now.

Instead, I believe we need to reflect with both humility and accountability about how our classrooms are speaking not only to the present moment, but also to the present needs of our students’ lives.

More often than we like to admit at times, we as teachers have a choice over what to center in our classroom.

Does the education system and its often-rigid pacing guides and obsession with standardized testing always support us in making the right choice? Of course not.

(Note: this might be the most realistic preparation we afford students for the “real world” in showing them how frequently we center what doesn’t matter and neglect what does.)

Still, I believe deeply we do quite often have a choice—and quite often we make the wrong choice, missing opportunities to center and celebrate the affirmation that everyone in that classroom, teacher included, very much needs.

“I think I give what I crave,” one student brilliantly noted in their poem.

As teachers, my hope is that we all can give our classrooms more of what we all crave—teachers and students alike—by centering affirmation with conviction much more going forward.

This is the most heart-warming newsletter ever :) It makes me want to have my history students write poetry just so we can also do this activity.

Also, Cloud Cuckoo Land is in my top-five favorite books also. Now I need to reread it.

What Jenna says! (I've read Cloud Cuckoo Land three times...it only gets better.)

The reverent silence of that library as students appreciate one another? Sacred. Thanks for this.