The Problems We Cannot Fix

and how that can weigh on those in the classroom

And for me, now as then, it is too much.

There is too much world.

This quote from Czeslaw Milosz serves as the epigraph of Emily St. John’s Station Eleven, which itself is a book that I am continually transfixed by each time I return to it—which I’ve done yet again of late in search of comfort amidst the "trudging” required to move through November as a teacher.

After all, if there ever was a month that had “too much world” in it, wouldn’t it be November?

The opening chapter of the book is just as remarkable as its epigraph, in my opinion: a paramedic-in-training named Jeevan attending a staged performance of King Lear recognizes that the actor portraying Lear is having a heart attack, and despite discouragement from audience members he clambers out of his seat, down the aisle, and onto the stage itself.

He turns out to be correct: the actor has indeed had a heart attack, and yet there is nothing that this paramedic-in-training is able to do as the curtain closes.

“No one looked at Jeevan,” the narrator observes, “and it occurred to him that his role in this performance was done.”

Just like that.

What resonated with me so much in rereading this novel recently was not just that Jeevan witnessed the tragedy unfolding but more importantly that he understood it so innately.

Yet even in trying to act upon it with that innate understanding, there was no difference to be made.

Which, I think, is far too often how it feels to be a classroom teacher these days.

As a teacher, there is too much—too often.

Every teacher has their own context to navigate as far as their classroom and building, and of course the obstacles within those contexts vary wildly.

Across that variety, though, I think you can divide these obstacles into two bundles: the challenges within the classroom itself and also those outside the classroom walls but still within your building—which is what one of my first ever Broken Copier posts touched upon over three years ago, a reflection on the advice I’ve often received to just “close your door and make your classroom good.”

Advice that I continue to have mixed feelings about.

But to take a further step back right now? Yikes. Just this week:

The Department of Education made a major move in its ongoing downsizing and destabilization, with many of its responsibilities being transferred to other departments. (As always, read Jennifer Berkshire on this.)

OpenAI released ChatGPT for Teachers, announcing numerous district partnerships and making the tools “free to K-12 educators in the U.S. through June 2027.” Of course, there’s a catch: you have to use your work email to get verified and receive access, which makes this a potential crossing-of-the-Delaware for AI companies and the public education system.

If these weren’t bad enough, on the more-local front, a budget crisis is poised to severely impact educational services in my own state: “the Oregon Legislature gave the agencies an assignment: draw out two budget scenarios, one for a cut of 2.5% and another for 5%.”

To recap: fewer federal protections and services for students, more power and influence for an AI company, and—at least in Oregon—potentially much less funding.

There is indeed too much.

And yet there is still so much good.

Not wanting to start our next full unit until after Thanksgiving Break, I looked ahead at a short stretch of flexibility in our sophomore English class and made a quick, two-fold decision: we would be closing our Chromebooks and instead opening plays.

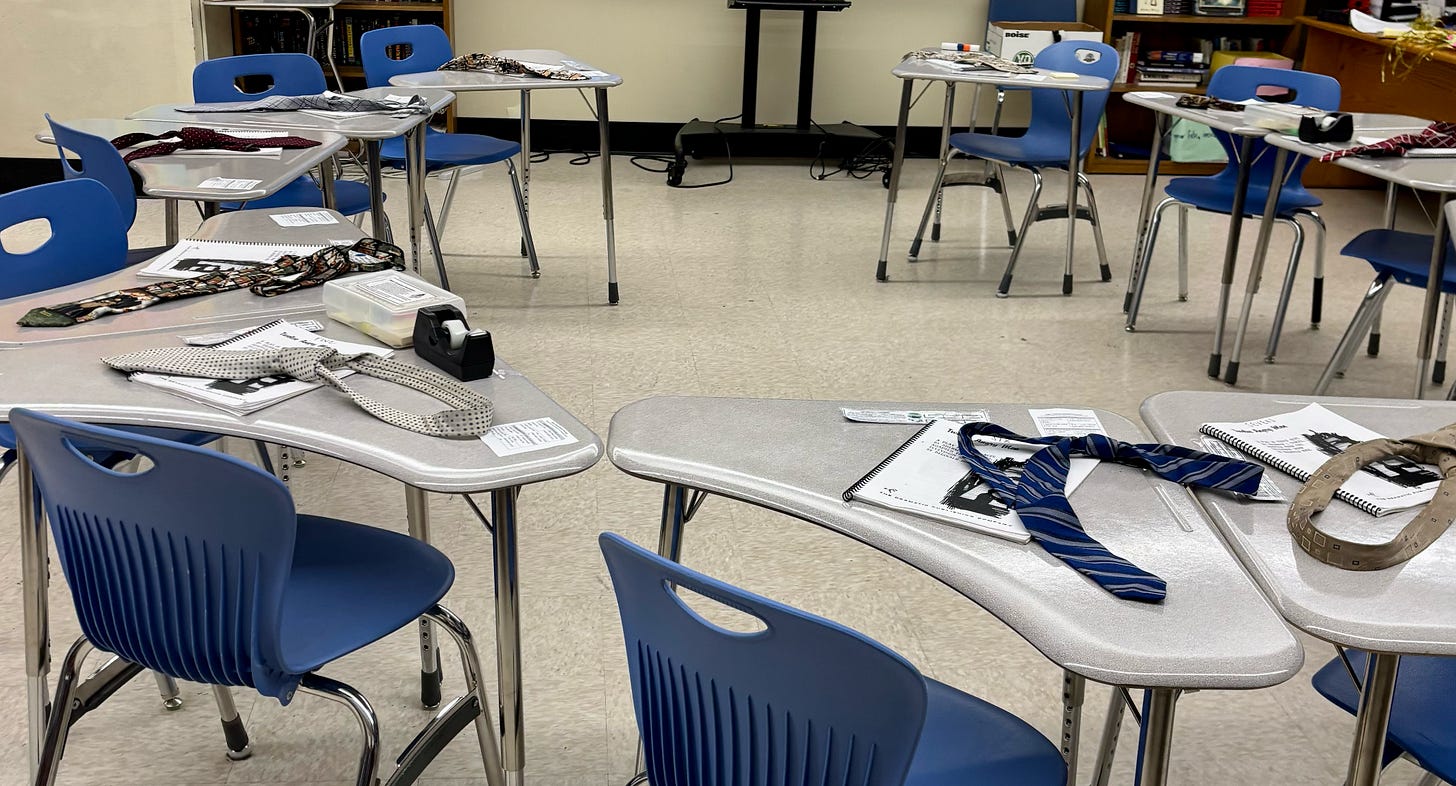

Borrowing supplies for Twelve Angry Men by Reginald Rose from a generous colleague, I watched the classroom almost immediately transform itself: a small circle of desks for jury deliberations, ties for each juror, and a plastic gavel to boot.

Just like that, a classroom culture that was without question falling into the normal November mire reawakened:

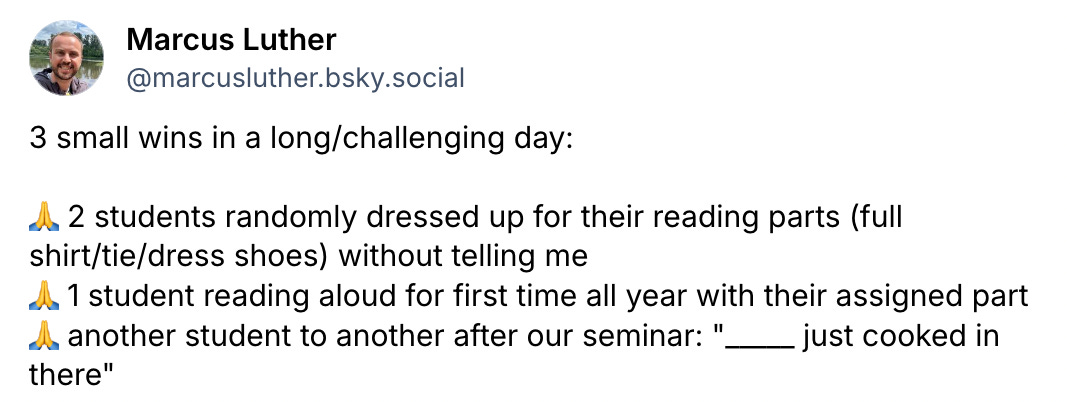

Multiple students decided to dress up on their own for their roles, walking in with coordinated dress clothes: “Mr. Luther, we don’t need your ties today!”

Several students who had previously gone a long stretch without saying a word or participating were suddenly in the center circle (!!!), reading aloud and even volunteering answers to follow-up questions.

The outer circle was following along with their “1…2…3…gasp!” directions, too, and contemplating some very-real questions related to the play: what is okay versus not okay with jury deliberations; whether an impartial jury is actually possible; and the very notion of reasonable doubt itself.

Most importantly, though? Students were smiling and laughing—yes, they were also learning!—and I was able to mostly forget about all those outside-the-classroom problems while the lively jury deliberations continued with increasing enthusiasm.

To abide between the good and the challenging?

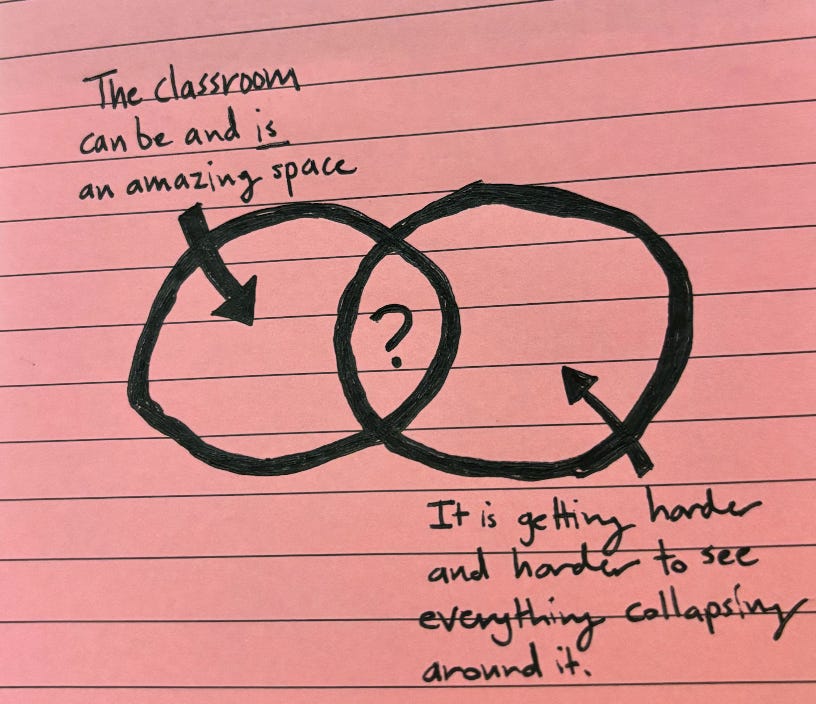

A little more than a year ago, as part of our slow-read of Alex Shevrin Venet’s Becoming an Everyday Changemaker I found myself sketching out “Vent diagrams”—intentionally leaving space in the middle as I grappled with that margin between hope and fear in the aftermath of the 2024 election:

That space between hope and fear, then? I believe it will matter more than ever in the years ahead, even as it is likely going to become more challenging than ever to live in that margin as educators.

A year later? Yep. Can confirm.

Which is why I returned, I think, to that very same activity in reflecting for this post, According to the creators, “A good vent draws out a tension that we don’t have language for because that non-binary overlap isn’t really part of our public discourse (yet).”

This week I did my best to think about the two things I feel most in this moment as a teacher—and to hold them both simultaneously:

The classroom can be and is an amazing space

It is getting harder and harder to see everything collapsing around it

We really do need language for that feeling as teachers, don’t we?

It takes a toll to see so many problems we cannot fix.

I don’t necessarily have a great answer to any of this, which is likely why I’ve set aside the drafting of this post several times to dive back into my yet-again-read of Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven.

The incredible irony of its opening chapter, I realized recently, is that Jeevan’s heroic-yet-ineffective rescue attempt occurs on the precipice of a worldwide pandemic that ends up wiping out most of its population.

It didn’t make a difference, but even if it had it likely wouldn’t have mattered.

I think one of the reasons that Station Eleven resonates so much with me as a teacher right now is that it grapples with what seeking hope can look and feel like in a context of hopelessness.

Perhaps the most memorable part of Station Eleven—aside from Miranda and her graphic novel, which I have already leaned on in a previous post—is the Traveling Symphony (pictured above): caravans of musicians and performers who continually travel from the remaining fragments of towns of the post-pandemic world to stage productions of Shakespeare.

“People want what was best about the world,” one of the actors says at one point when asked why they only perform Shakespeare. On the lead caravan, there is a phrase affixed to their banner: Because survival is insufficient.

For me, the idea of a caravan traveling cyclically from destination to destination this this fictitious post-pandemic world, trying to share their art, trying to perform stories of what was and still is good, having determined and then pronounced that survival by itself is insufficient?

That resonates a lot.

The work of being a teacher is heavy enough with all the students we see who are struggling in ways beyond our capacity to support. It is heavy enough on the days when we admit to ourselves that our classroom is not enough, no matter what we pour into it. It is heavy enough when it feels like you just might have a solution, even a small one, only to be reminded yet again that the systemic issues of education are incredibly, infuriatingly stubborn.

Add in that adults are choosing to break down critical federal protections, no matter the consequences.

Add in that tech companies see potential market share in education to grab hold of, no matter the consequences.

Add in that funding already is not enough and, at least in my state, could be diminished even further.

No matter the consequences.

But what else is there to do but perform the good?

A colleague pulled me aside earlier this week in the hallway.

“Did you see what _____ wrote?”

As soon as I could, I found my way to my own computer to check what they were talking about, and saw the student’s reflection on their school day that they had written: “Language arts…your very ‘favorite’ class: taking notes, writing stuff…but actually, you’re working on a play right now which is pretty interesting.”

You’re working on a play right now which is pretty interesting.

This other teacher knew how hard we had been working for the past two months to find something to get this student to “click”—and this week was the week it happened.

I already knew, having watched them in the classroom reading aloud with their haphazardly-tied tie and laughing aloud when the plastic knife was revealed and clicking, at least for this week, in a way that matters.

Yet reading that confirmation, that small little acknowledgment amidst an education system outside the classroom that feels like it is perpetually collapsing from too much?

I’m reminded of what Jeevan admits to himself after failing to revive the fallen performer in that opening chapter of Station Eleven, how even after witnessing that tragedy firsthand he felt refueled within his conviction to become a paramedic:

“At moments when other people could only stare, he wanted to be the one to step forward.”

I don’t want to just stare, even amidst all this, because staring is insufficient.

There is good to step forward towards, in the classroom and beyond it.

There is good to be performed.

Three Closing Recommendations

Building on this new “norm” with Broken Copier posts, here are three things I’d recommend checking out based on what I’ve encountered and found helpful as a teacher in recent weeks:

Something to read: “Classroom 2040: What AI Futurists Can’t Teach” by Stephen Fitzpatrick — Stephen continues to be incisive in calling out the ways we are falling short in this AI moment, in a way that I’d argue that everyone—no matter your perspective on AI—can agree with.

Something else to read: “What Went Wrong” by Peter Shull — I don’t want to spoil this post, one that has lived in my head all week, so I’m just going to say to trust me and set aside time to read it. It will be worth your time.

Something to explore: a Bluesky Slow-Read of Macbeth! — Look at me coming full-circle with the Shakespeare mention earlier in this post! Long story short, each Sunday on Bluesky we are going to chat about Macbeth, especially from the lens of what it can be in the classroom. Any are welcome to join!

So glad to find another Station Eleven fan! Whenever I travel I always scope out my future residence in the airport, just in case :)

Hang in there, Marcus. I thank you for taking time to share your thoughts, feelings, hopes, and fears.

I don’t know where we are headed, but where we were/are could no longer be sustained.

Alongside teaching full time, I mentor educators in my content area going through credentialing ed & county programs and I can tell you that these younger teachers are hungry to go beyond Kahoots and Tik Tok; they want to actually teach, they want to learn to do differently, and it’s really refreshing.

It’s also exhausting for them: to be paying for these ed programs and out not knowing how to design instruction for learning or transfer of learning.

I think the cognitive dissonance which will be required by all is to take a step back besides partisan lenses and say: yep, that doesn’t work. Yes, that’s uncomfortable, but parents this is what it means. Etc.

I can also tell you that I have taught in rural, urban, charter, private in 3 states (sharing this not as a matter of pride; it’s a result of circumstances) and in the end no matter the storms and upheavals on the outside, the decisions made by the local boards within the confines of what a state allows and doesn’t makes all the difference.

Local leadership often needs the boot.

I say that fully aware: well, who does one replace them with?

It’s a curricular problem and when something remains circular this many decades—something’s gotta give. sometimes we go in the wrong direction (too early for me to make that call) before course correcting. but it’s better than standing still.

Have a restful Thanksgiving holiday break!