When a student refuses to...

responding to individual student challenges early in the school year

It is the first day of school and, for once, everything is planned out perfectly.

(Yes, this is a hypothetical. Stay with me.)

You have crafted an opening lesson that contains a mixture of welcoming activities and clarity around what will take place in your course; you have set up your room thoughtfully and triple-checked the latest version of your rosters; and you yourself are filled with authentic enthusiasm by the time students walk in.

You are excited and confident and determined to begin building a great foundation for your classroom starting Day 1.

Then it happens: five minutes into your first class period of the school year, while the rest of your classroom is going along just fine with the brief reflection activity you are beginning with, you notice that one student is just sitting there.

“Do you need a pencil?” you ask quietly, ready to provide one. (You’re not messing around this year: you made sure to have an arsenal of pre-sharpened pencils for the first day.)

Head shake, no eye contact.

“Want me to walk you through what to do?” you ask, kneeling down and still remaining quiet. “I know the first day can be a lot, at least for me.”

Head shake, no eye contact.

Now other students are finishing their written reflections and, expectedly, are beginning to await next steps. After all, the countdown clock for this activity that you added to the slide deck—seriously, you’re so prepared!—has less than a minute remaining on it. A few students already done glance over at you kneeling down next to the student who is refusing to participate.

An intrigued audience to this interaction between you and the one student in the classroom who refuses to go along with the rest.

What do you do?

Seriously: what do you do?

If I’m being 100% honest, I’m really writing this post from a place of self-interest as I get ready for another school year and try to imagine in advance my best self as a teacher in scenarios like this one.

These moments happen and, when they happen, these moments can be immensely difficult—and therefore are worth reflecting on, right?

In this post, I want to move through five different lenses as I reflect:

Why I think “100% culture” makes these moments even harder

Three questions I try to ask myself before I respond

What I do when my own response does not work

The overarching priority that I always try to come back to

One final point that ties back to “100% culture” before signing off

The problem with “100% culture”

I believe one of the reasons that a moment of a student refusing to work is so stress-inducing as a teacher is that in recent decades there has been a meetaphorical (and sometimes literal) megaphone shouting the phrase “100 percent” and making us feel like failures as teachers whenever it does not happen in our classrooms.

Take Teach Like A Champion, for example, a text that has become its own culture in education. In the words of its founder, Doug Lemov, the goal is to “ensure that 100% of students are with you for teaching and learning, 100% of the time, 100% of the way.”

Even setting aside the more extreme examples of this, Teach Like A Champion is far from the only place you’ll hear this mindset. From phrases like “all means all” and “no excuses” to arguments that the most important thing for our classrooms is maintaining high expectations, as a teacher the message is pretty clear: if a student is unable to succeed in your classroom, it’s on you.

(I’m sure it is a coincidence, too, that folks who are saying this are very rarely in the classroom themselves. Definitely a coincidence.)

Still, even as I can easily name my pedagogical differences with this “100 percent” culture of education, fourteen years into teaching and I cannot fully shake its influence and, consequently, judgment.

So when I see that student early in the school year opting out of an activity, or potentially refusing altogether to participate in a lesson, this is what that little Teach Like a Champion voice is telling me:

I’m failing this student right now. It’s my fault.

Which does not help me respond the way I need to. Not at all.

What I try to ask myself in these moments

Deep breath, though. Doug Lemov isn’t in my classroom.

I am.

So what do I do?

Every context is different, yes, and I certainly don’t presume to know what you reading this should do in your own classroom—but I do find it really helpful to ask myself these three questions in these moments:

Self-check first: where am I emotionally? There’s a lot of energy in those early weeks of school, including understandable, self-induced pressure to get off to a good start. That’s why it is critical to be self aware, I think, about the emotions you are experiencing as a teacher before you respond. Name and acknowledge them to yourself, then move to the student once you’re ready—as way too often students end up facing the consequences of our own negative emotions as teachers.

Is there a way for me to understand more? We all know that there is always a why behind the what—and in a moment of a student refusing to opt into what the rest of the class is doing, trying to understand more about that why is really important. There are different ways of doing this (I talk through more of these in the video below) but I believe approaching student refusal from a place of curiosity is the best entry point to these situations.

How is it impacting the rest of our classroom community? Particularly if it is in those early weeks of school or an unusual choice by the student based on your experiences, the other thing I’d suggest is to assess how one student’s refusal is impacting the rest of the room. If it is disrupting the learning of others in the room, that’s one thing—but also keep in mind that sometimes we ourselves as teachers make it a disruption in how we respond. If it’s not negatively impacting others (it usually isn’t!) then you have some flexibility that isn’t worth forfeiting by overreacting in the moment.

Here’s a bit more elaboration via video on why I feel like these three questions are really important in these moments as a teacher:

Okay—so the student is still refusing, though. What now?

Here is where I will contradict myself a bit: completely ignoring a student’s refusal in your classroom is not a solution. Beyond trying to check in with them and understand what is going on, here are the two things that immediately become a priority for me if I can’t get them back on track in that lesson:

Don’t try to solve this alone. In those initial weeks, it is all-hands-on-deck in trying to figure out how to support a student struggling in our classroom. I check with previous teachers and counselors and family members and coaches and really anyone who can help me get a clearer picture of what will help this student the next time they walk into my room. Two reasons why I believe so much in doing this: [1] it gets you away from “savior mentality” and instead acknowledges in your actions that you need and want support; and [2] it shows the student how invested you are in their success by being able to name to them the different steps you have taken to get them support. (Not to mention? It is a great way to build your own network of people in your school and community! A win in the short term and the long term, if you go about it the right way.)

Have a plan for next class. The worst thing you can do—and I say this from many iterations of personal experience, I assure you—is to just cross your fingers and hope that the problem will go away the next time the student shows up. What that “plan” looks like? Incredibly dependent on the situation as well as your school resources and systems, but my recommendation is to find some way to connect with that student in a way that [a] acknowledges what took place and more importantly [b] reiterates your belief in them and goal of making sure they feel supported in your classroom. (My go-to? Write them a note!)

Which gets to the most important thing that I’m reminding myself again and again and again going into a new school year…

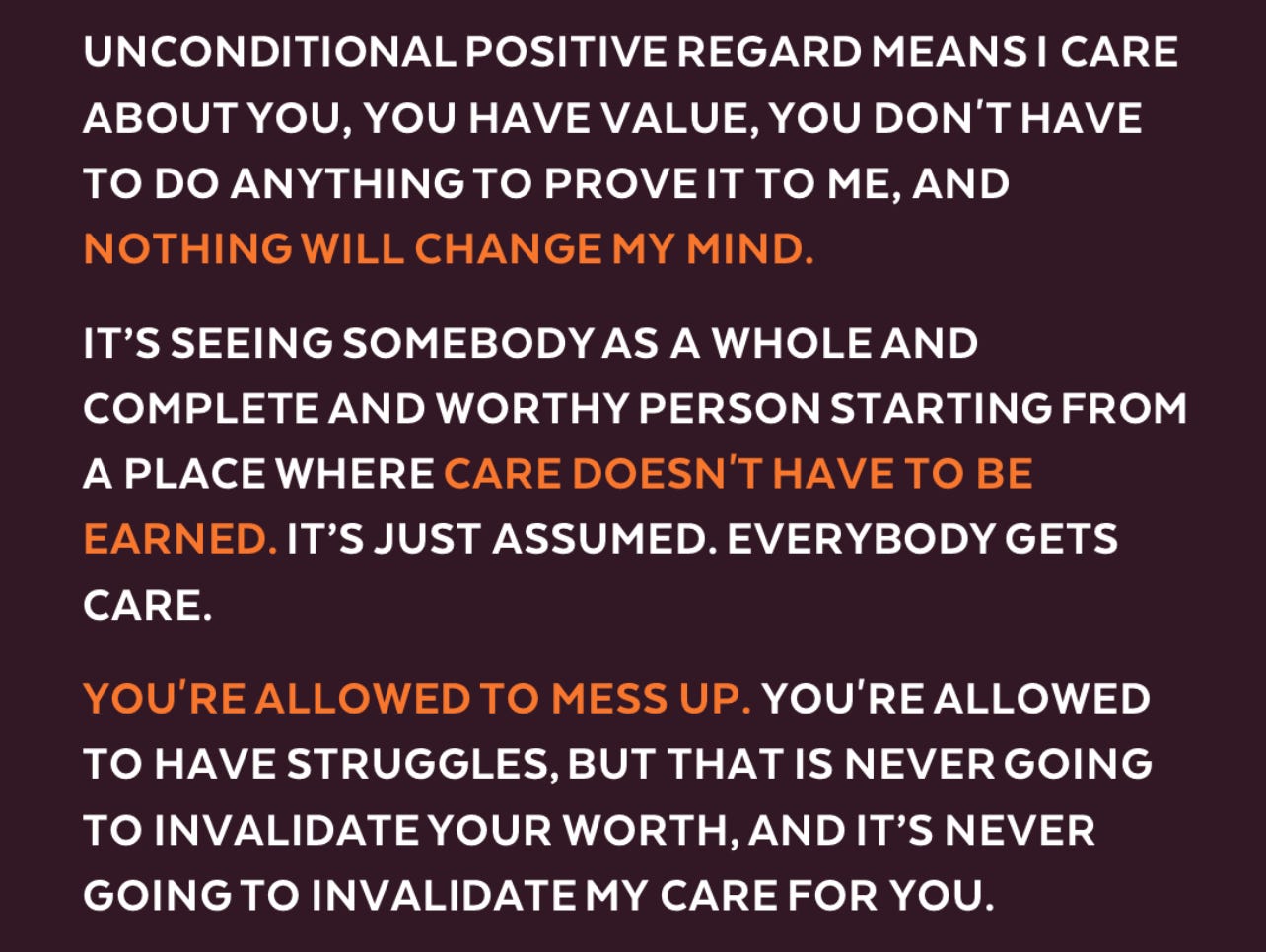

My North Star? Unconditional Positive Regard

This is a 100% that I can sign up for: the idea that all of our students deserve to be treated with unconditional positive regard no matter what took place yesterday or last week or last year—and that, in the words of , “I have to do the emotional work [as a teacher] to maintain perspective, I have to let go of my own ego.”

Of course, typing those words out is considerably easier than doing that emotional work and setting aside our ego as members of a teaching profession that is constantly, increasingly under attack.

But at the end of the day, unconditional positive regard towards all of my students, especially those who are struggling, is a standard I’m willing to hold myself accountable to.

And to take it one step further: my goal going into this year is to make that unconditional positive regard explicit and transparent—if students don’t know and feel it to be true, then I need to do better.

So when a student is refusing to participate or has their head down, what will I do?

I will make sure they know that there is nothing they can do to change my mind about their value and how much I care about them as a person.

From there? We’ll figure it out.

“Hopefulness is not a neutral position”

One more thing.

To circle back to the “high-expectations-solves-everything” edu-messaging I complained about earlier in this post, I do believe that a lot of that messaging is coming from a well-intended place, responding to an education system in which too often students have walked away feeling as if the adults around them stopped believing in what they were capable of.

They’re right: that is a problem that needs to be addressed.

Yes, far too often that “100 percent” messaging is too simplistic, sometimes to the point of gaslighting; and if you’re frustrated with folks who have left the classroom acting like all it takes is having high expectations for all of your students, then join the club. I’m right there with you.

But there’s a kernel of truth in the messaging of high expectations for all students that I think could be much better framed as committing to hopefulness towards all students.

Not just in our beliefs as teachers but in our actions.

A year ago in an interview with Stephen Colbert, Nick Cave shared a response to a letter he received from a fan struggling to find a positive outlook in the world:

Unlike cynicism, hopefulness is hard-earned, makes demands upon us, and can often feel like the most indefensible and lonely place on earth. Hopefulness is not a neutral position. It is adversarial. It is the warrior emotion that can lay waste to cynicism […] It says the world and its inhabitants have value and are worth defending. —Nick Cave

Last week I was one of hundreds of educators sitting in a conference center ballroom, being “talked at” by a presenter, hearing a lecture that hope is not a plan. Repeatedly, with gusto.

And there I was, shaking my head. They lost me.

Because while there are many things I do not understand about teaching, there is one thing I do know: there are few things more powerful than hopefulness, and how much students need their teachers to cling to and act with hopefulness every single day. It is adversarial in the best of ways, imagining a better version for tomorrow than today and acting in accordance with that imagination.

In the words of adrienne maree brown, “We are in an imagination battle.” In the classroom and most certainly beyond that. A battle we must win.

So I’m going to choose hopefulness as a teacher, as an idea and an action.

Even when a student is struggling in the classroom.

Especially when a student is struggling in the classroom.

Note: featured image for post from Pexels.com, taken by Ann H

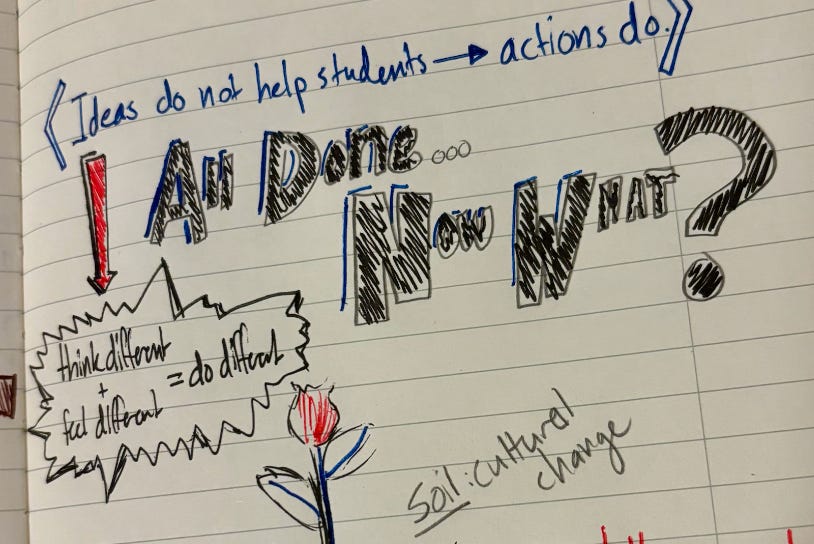

Great post, Marcus. We've all been there. I like the image call-out from your notes - "Ideas do not help students --> actions do." You have to do something and, for non-teachers, this is what they may not realize is that one kid will keep us awake and trying to figure it out, probably all year long. The other advice is crucial - talk to other teachers, counselors, administrators, and coaches - anyone else who has contact with a struggling student. Early in my career as a younger teacher, the idea of a kid not doing well in my class felt like I was the failure. With many more years under my belt, I know it's far more complicated. We have a mantra at our school (applied to students and adults alike) - asking for help is a sign of strength and not weakness.

I don’t see or hear any contradictions between anyone you have quoted nor your approaches and thinking not aligning with one or the other.

I don’t think we can do this without hope, high expectations is hope, and meeting the student who refuses to do anything day 1 is hope, and reaching out to others is hope.

I did have a student like that two years ago. Because she was not disruptive, we agreed that as long as her head was not down on the desk the entire time, she could write or draw whatever she wanted. She wrote and drew nothing that would give me or her any insights. There were no parents. One aunt. Eventually, she had to move since she was not supposed to be in this district to begin with. It was an 8-10 person job daily —all resources on her— to make sure she was not disruptive to others etc.

Two years later she came by to see us all. She wanted us to know it mattered we cared, that she didn’t know any strangers who had ever cared for her. She was planning on dropping out of high school after 9th grade. The work was too hard, she said.

Last year we also had a boy like that.

Those are the ones I know and interacted with. There are so many more who have not done a single thing since 5th grade despite team meetings, and guardian conferences.

I have hope that we will start to address this in 3rd grade when it begins. That perhaps we will have schools within schools for students who throw in the towel starting in 3rd grade .