Yes, Teachers, You Should Be Panicking About AI

Six reasons I am "planting my flag" that artificial intelligence's development is going to drastically change education—and that we aren't even close to prepared for it

In our final unit of the previous school year, I introduced our multi-genre projects—in which students are asked to synthesize “genres” of narrative, analytical and creative writing alongside audio and visual components—with a simple rationale:

“All that ‘writing within a box’ that your K-12 experience has largely been defined by,” I told them from the front of the room, “will someday be replaced by artificial intelligence.”

Less than six months later, it’s here. (My first reaction? Welp. I was hoping for at least another half-decade before this moment.)

With the recent release of ChatGPT, an open-source artificial intelligence writing platform that can do, well, just about anything you ask it to do to a relatively-impressive degree of quality (and by the way, if you haven’t yet gone and played with it, stop reading and go find yourself falling down a sublime mineshaft of cynical awe) it is undeniably clear to me that everything is about to change, and change rather quickly.

Especially for education.

However, when discussing this online and in-person with other teachers, I find myself to be the outlier. Most educators seem only mildly concerned, if at all—even those who have spent time with it seem to be more focused on nitpicking its current shortcomings rather than, in my eyes, reasonably considering the seismic impact this will have on what education is.

My panic level, someone asked?

“A 12/10,” I answered. And that’s probably understating it.

I hope I’m just another version of William Blake’s “voice crying alone in the wilderness,” but I don’t think I am.

Here’s are six reasons why:

Reason for Concern #1: we aren’t always honest enough about how much “standardization” is built into education

One of the more common reactions I saw online over the past week was for teachers to speculate about how the ChatGPT examples lacked the nuance and authenticity of actual student writing—and I’m sure many of those teachers, like I do myself, immediately pictured the most memorable writing samples from students who walked into the classroom with that uncanny ability to breathe their own voice into whatever writing they were asked to do.

But I co-sign what fellow English teacher Daniel Herman “confessed” in The Atlantic in a must-read piece:

“Let me be candid (with apologies to all of my current and former students): What GPT can produce right now is better than the large majority of writing seen by your average teacher or professor. Over the past few days, I’ve given it a number of different prompts. And even if the bot’s results don’t exactly give you goosebumps, they do a more-than-adequate job of fulfilling a task.” —Daniel Herman

Simply put, a lot of what we do as teachers is about helping students build the skills to respond within expectations and constraints—expectations and constraints often that are meant to help “prepare them” for later expectations and constraints, within the education system and beyond them.

Standardized tests are a part of this—more on that in a later rationale in this post—but so is the very understandable fact that part of communication is learning to do so within shared norms and contexts that everyone adheres to, relatively speaking.

And that, unfortunately, is the exact type of thing that this type of program can already do.

Want to see an example? Below is a prompt that sophomores completed a few weeks back in their rhetorical appeals mini-unit that I simply copied/pasted—without making any edits!—into the ChatGPT program:

In seconds, this was the result. (Oh, and I just did a screenshot of the first part of the post—ChatGPT actually knocked out all three appeals with a concluding paragraph)

I don’t think of the above-prompt as a “low-caliber” prompt, either! But the response within seconds was able to demonstrate the skill I was asking students to perform after two weeks of instructions, and that’s without any edits or specific instructions to improve its quality.

Are there some prompts this program currently struggles more with, especially with newer articles it cannot currently look up? (It is limited from searching for anything more recent than 2021 publishing at the moment.) Certainly. But even on its worse efforts, you can then give it more specific instructions or additional information and get something reasonable. Or even proficient, as the above-example demonstrates.

Perfect? Of course not—but that leads to my second concern…

Reason for Concern #2: the incentive to use AI tools as a replacement for original writing will be highest for our students who struggle the most (and most need support!)

Returning to the point Herman made in his article in The Atlantic, I don’t think educators are being honest enough about the level of writing they regularly get from students.

Think about the students who have fallen behind and have piles of make-up work to get through, or those who have been finding ways to “get by” for years while being significantly-below-grade level as readers. Think about students who struggle with dyslexia or a host of other disabilities that make the writing process 10x longer and more challenging for them than the average student—not to mention those who are arriving at English as a second language and trying to play “catch-up” with peers.

I offered a sample of two relatively-solid student narrative pieces alongside two artificial-intelligence pieces generated by the exact same prompt the other day, and once again, yes, if you squint enough, you can probably tell the difference!

However, what I didn’t post were some of the lower-level narrative pieces—some a result of skill gaps, some perhaps just rushed last-minute. And that’s my point with this concern: the AI pieces were significantly better than those pieces, and therein is the dilemma that concerns me: the struggling writers are the students who have the greatest incentive to use artificial intelligence to mask the gaps that need to be addressed.

Just to be incredibly clear about this, too, plagiarism software cannot check this.

(Could you interview a student and maybe coax an admission out of them if the writing was too dissimilar from previous writing samples? Perhaps. But are you going to do that for all 100-200 of your students on every constructed response? I don’t think so—and that’s not even considering that, once these tools become normed, there will be no lower-level previous writing samples to compare to for many…)

Oh, that’s before you bring in the “elephant in the room” of all education discussions, unfortunately, that I am trying to not think about too much, given the stakes…

Reason for Concern #3: think of this as a steroid to the entire standardized testing industry in the worst of ways for all involved

Fact: standardized testing already drives so much of what education looks like in our country, and increasingly has done so since the implementation of No Child Left Behind a little over two decades ago.

Fact: standardized testing relies primarily on multiple-choice questions for efficiency and cost-saving purposes—something I have been highly critical of as this is an inferior way of assessing learning.

Fact: standardized testing will be highly incentivized financially to be “ahead of the game” in understanding and implementing this technology into everything that they do.

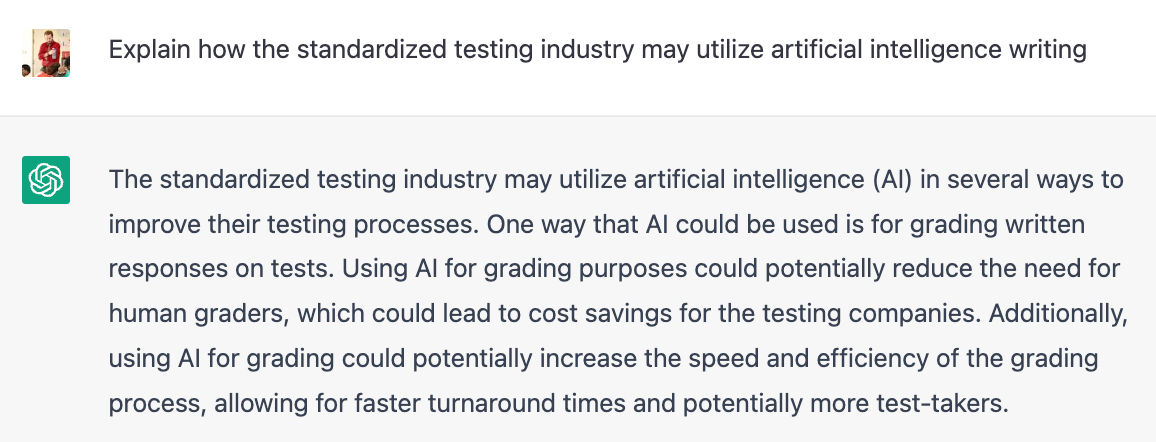

How do I know? Well, I asked our good friend ChatGPT:

I repeat: “allowing for faster turnaround times and potentially more test-takers.”

In other words, more tests and more money. Brilliant.

However, as Jim and I discussed in our most recent podcast before the release of ChatGPT (wasn’t our timing pretty incredible?), even the types of tests that we think of as “upper-level” such as AP Exams confine students to rubrics that are essentially "boxes” that you train students to write towards—knowing that the human graders are crammed into rooms trying to speed through thousands upon thousands of them each summer as efficiently as possible.

And that is where I take an even deeper gulp, because the infusion of artificial intelligence in these high-stakes tests will very likely increase the incentive for these tests to be even more “standardized” in the types of writing they expect from students.

—which will put us as teachers in the worst of logjams: being tasked with preparing students for assessments with steroid-injected dosages of standardized writing at the same time that artificial intelligence is making that type of writing essentially worthless.

Concerned yet?

If not, how about this:

Reason for Concern #4: for many educators, there will be an instinct to “fight back”—and that fighting back will make education worse, too.

“See, that’s why we were right about cursive!” say those teachers.

Okay, that is an overstatement.

But already many of you reading this post know exactly how a considerable portion of teachers will respond to the proliferation of this technology into the hands of students:

“Computers and phones away,” they’ll say. “Pencils out, paper out. Here we go!”

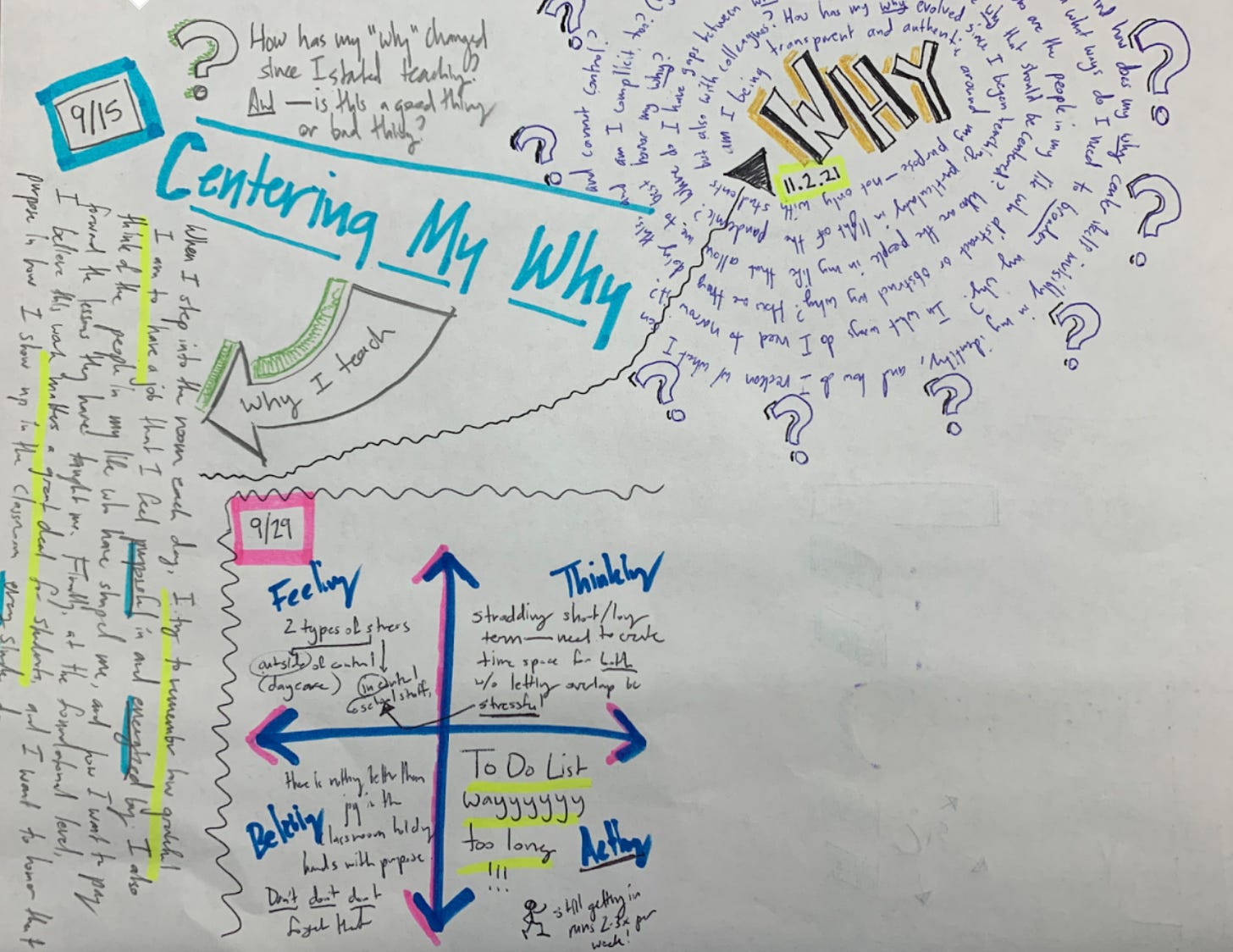

Trust me, especially after nearly a year of teaching over Zoom, I recognize the value of making learning tangible—remember, I’m the guy who has students physically mindmap their reflections every two weeks, right?—but I also have a major problem when we implement and require a form of nostalgia rather than preparing students for the world we are already in.

This is not a fight we will win, no matter how many millions districts will invest in “AI-detecting software” (and yes, for-profit “education” companies will find a way to make far too much money off this, too) or how many reams of notebook paper are wasted in the futile fight against a technology that very much needs to be collaborated with rather than combatted against.

Nevertheless, after a decade of getting to know educators and already hearing the conversations out there, there will be a sizable contingent that decides to wage this war—and, in doing so, will widen the already-wide gap between the education experience we provide to students and the world they are already in the process of inheriting.

So yeah, I’m concerned. The realistic (and, in this case, quite cynical) part of me is fairly confident that the way we respond to artificial intelligence as an education system, especially in the years ahead when it becomes normed and advanced, is going to do much more harm than good.

Speaking of harm, though…

Reason for Concern #5: education is already rife with equity issues—and this has the potential to become another, quite-egregious one

If you aren’t convinced yet, take an imaginative stroll with me.

You are a parent of a student who is about to enter high school, well aware that the academic success of your student in these formative years often can create a direct line to status and opportunities afforded to them after high school and throughout the rest of their lives. How they do in high school quite often shapes the rest of their life.

Luckily, you have the financial means to purchase an artificial intelligence software program for your student that is far superior to those available open-source, and you are fully aware that your student will benefit in major ways academically from this and that many of their peers already have this program at their disposal.

Do you purchase it?

Of course, the answer is yes—just like so many with means pay for personalized tutoring, additional test prep courses, summer programs aligned to admission criteria, as well as so many other advantages they “pay for” invisibly as far as the advantages their students have in not having to work that extra job or not having to babysit for siblings or not having to deal with food insecurity, temporary homelessness, or the myriad other obstacles that students they sit in class next to face—that is, of course, if you haven’t already purchased the advantage of an entirely-separate private school experience for them, too.

We already know that companies like Google have better artificial intelligence technology than the open-source offerings like ChatGPT, so I think it is very fair to assume that the “open access” tools will not be able to keep pace with those higher-quality versions available…for a price.

And given everything we already can imagine about the game-changer that is artificial intelligence as a readily-available tool in education, now imagine that students have different calibers of tools based on their socioeconomic status, drastically exacerbating gaps that are already drastically exacerbated by so many other systemic contexts.

I’d call that concerning.

But then there’s the final concern that, quite honestly, I think you’re foolish not to admit to…

Reason for Concern #6: this technology is just getting started—and there is no reason to think it has a ceiling as far as sophistication, nuance, and creativity.

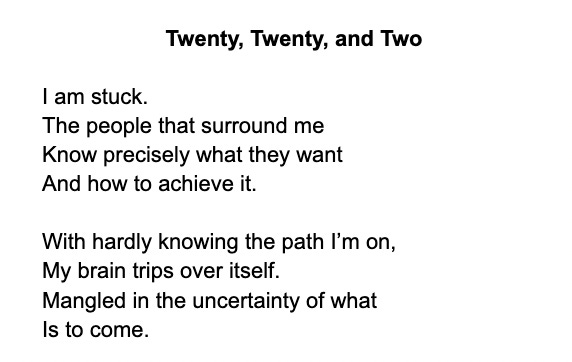

I’m gearing up next week for students to write their narrative poems for one of my all-time favorite classroom experiences: the peer-affirmation gallery walk. Last year, students wrote extraordinary pieces as far as authenticity, insight, and innovation. I mean, just look here…

And then again, here:

These are poignant and powerful and, in an undeniable way, pure. It is an absolute privilege I admit, time and time again, to see what students can do with a pen—or a keyboard, admittedly—and how they can push my own thinking of what writing itself is.

And can be.

But what happens when ChatGPT and the myriad superior iterations to come after it starts approaching this level, and then moves beyond it?

That can’t happen, though, right?

There’s an understandable, defensive arrogance coming from so many educators right now, pointing out the flaws of the current iteration and clinging with either a conscious or unconscious desperation to a normalcy, I’d argue, that now ought to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with nostalgia.

Chess players scoffed at the skill of artificial intelligence at one time, too, right?

This is why I’m trying to approach this with utmost humility, as I don’t think—even in my clearly-outlier alarm-raising—that I have a grasp of how much of a paradigm shift this will ultimately be.

I did take some time today, though, to play with the narrative prompts students will have in front of them this week—the same prompt that led to the poignant student poetry showcased above. Here is a complete (silent) video clip of me messing around with this tool today during my lunch break.

This stanza midway through of course sent shivers down my spine:

But I cannot stand the ocean,

The way it roars and crashes,

The way it pulls me in and threatens to swallow me whole.

The final couplet that it arrived at, though, after some poking and prodding as I tried to see how little effort it took to “personalize” a poem using this tool, felt like ChatGPT was talking to all of us educators in this moment:

But where will I be tomorrow?

Where will I call home?

Level of concern being a 12/10 feels like a drastic understatement for this moment, I reckon. I hope I’m wrong about the paradigm shift and our lack of preparation for this moment in education, but I don’t think I am.

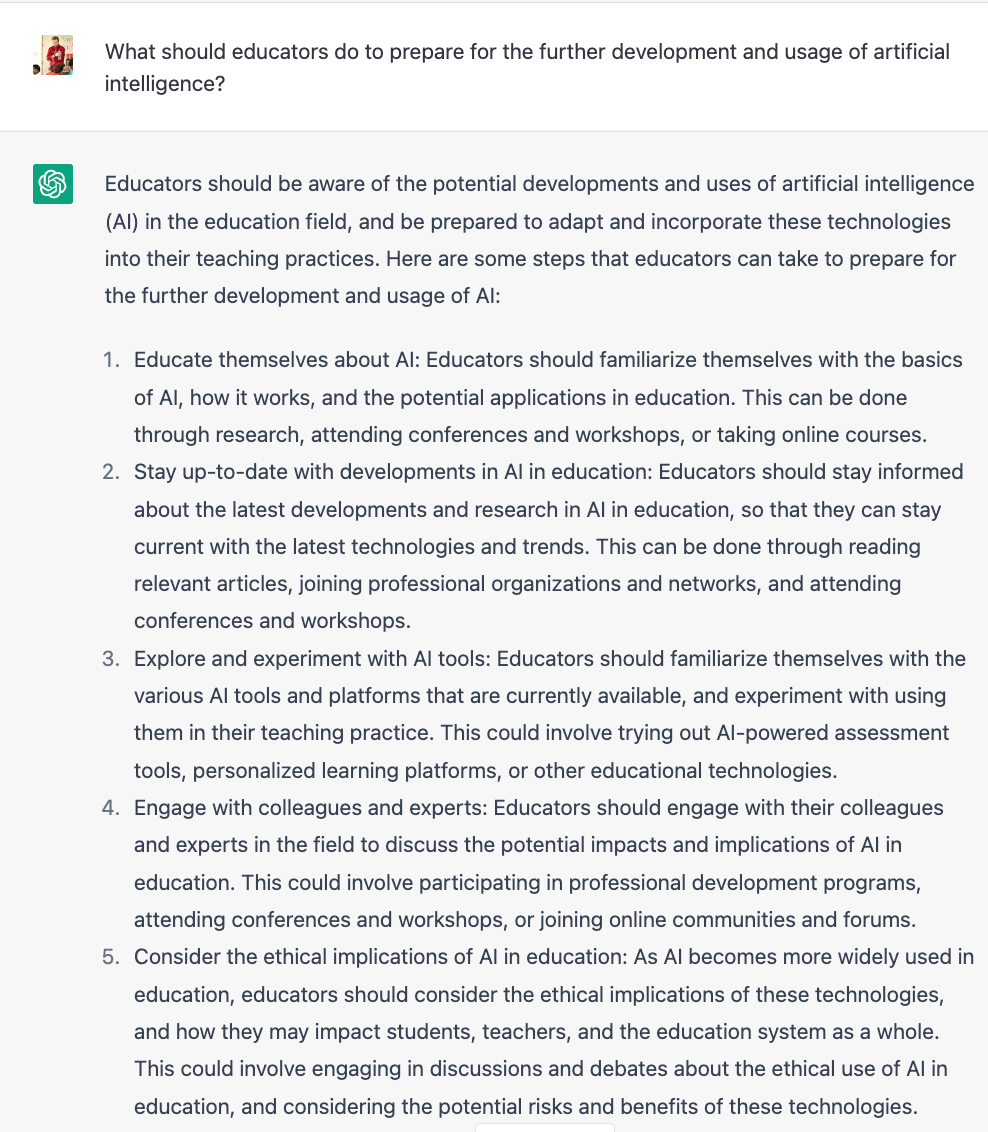

So what do we do, then?

I don’t really know, quite honestly, but I do believe the first step is to be more humble and intentional about having the pragmatic, pedagogical, and ethical conversations around artificial intelligence right now that we should have been having yesterday—and probably five years before that.

Like all other things education, people are going to have vastly different opinions and will enter into those conversations with divergent lived experiences and values, too. These won’t be easy conversations and consensus is hard to imagine any time soon.

But not talking about this isn’t a solution, either, so I’d prefer the hard conversation rather than the silent one.

In the meantime…

Damn, I made a Substack mainly to rant about this very topic - yours is great and I heartily agree with every nuanced point here