More Meta-Reflection in Student Writing

Why I'm trying to have students reflection on their own choices as writers more often

One of the first lessons this school year included a video clip from the most recent Minions: Rise of Gru movie:

I assure you, this group of AP Literature students were quite surprised to see an assortment of Minions-related comedy inserted into the slide deck—as was the assistant principal who had chosen that precise moment to pop in for an introductory visit! (side note: those “pop-in observations” are always at the most particular of moments, aren’t they?)

The point of this five-minute “intermission” to our work, along with some laughs?

That everything is a choice with art, and we need to frame our analysis of literature as such

My assistant principal, who taught English himself for three decades, nodded quietly at the back as we pivoted to that point. This has quickly become the “Minions Rule” in our class, which we circle back to not only in written analysis but also in our annotating as well as seminars:

Everything is a choice—and we need to do whatever we can to interrogate those choices…including their own choices as writers.

Why I Used to Struggle With This

I think if you polled 100 English teachers, roughly 100 would agree that it is important for students to consistently practice self-reflection as writers. I know I wouldn’t have thought twice about that from Day 1 of my own career (now more than a decade ago, as my receding hairline attests to more fervently with each passing day).

But if you walked into my classroom in previous years, or even looked through a collection of the past year’s student writing samples, you would see very little tangible evidence of self-reflection by students.

The biggest roadblocks, in my opinion?

a failure to build it into systems

a failure to prioritize it with time in class

Systems and time, no big deal right?

Well, actually, if it doesn’t happen at the beginning of the year, shifting a system in a classroom can be like turning an oil-tanker 180 degrees—and any teacher knows how scarce time can be, and that’s before the inevitable variables end up draining even more in-class time as the year progresses than you had planned.

The good news: by creating a system—even with your very next writing assignment!—the allocation of time becomes much more doable, and that’s why I think it begins with how you design and norm writing in your room:

Building in Self-Analysis on Writing Choice

I’m a fan of Google Docs for many reasons as an English teacher, but first and foremost is probably my ability to create templates for students to work through in their writing process.

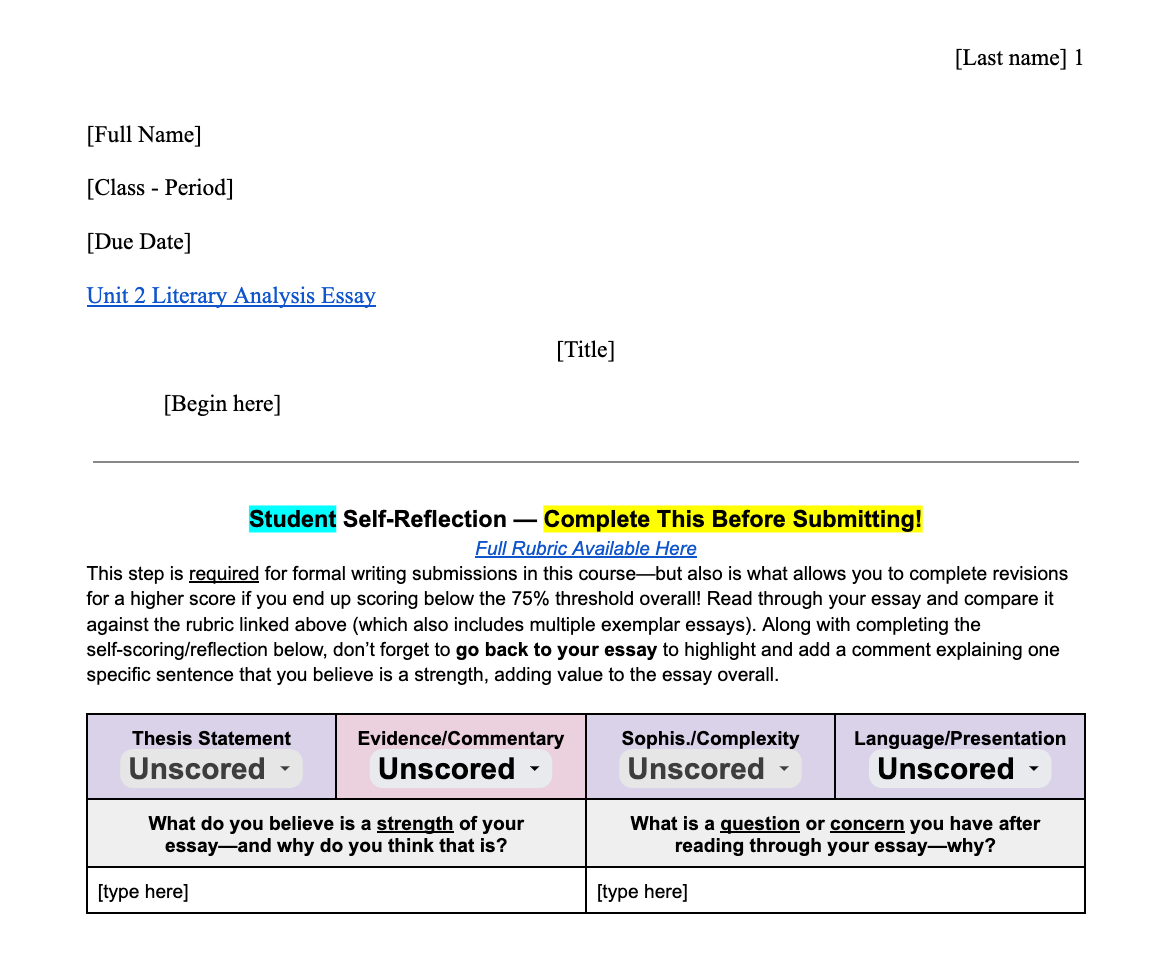

I’ve shared other examples of this via The Broken Copier, such as the self-analysis that students complete on analytical essays, but here is an idea of what students encounter with their “blank templates” in our class:

At the end of the day, there are choices we make as teachers, too. Rather than prioritizing “formatting” with students having to create the document from scratch, I wanted the emphasis to be on their actual writing process, which is why they literally see the self-reflection space right away on their document.

The goal: by building it into the document itself—each time, not just once in awhile—self-reflection becomes inextricable from the writing.

In past years, this more often would look like a think-pair-share reflection after essays were written, or maybe some questions to add to their spiral notebooks about the essays.

Reflections that I rarely saw or heard.

So my first piece of advice is rather straightforward: if you want students to self-reflect on their writing, build tangible space for that self-reflection into their writing process, and then protect time for it to be completed by all your students.

However, I don’t think this is enough—and overall meta-reflection doesn’t mean nearly as much as it is confined to a single type of writing. Therefore…

Framing “Choice” Across Genres of Writing

The best part about the word “choice” is that it automatically brings up the idea that there are myriad choices that writers make at every interval—and this lens matters not just as critical readers of literature but also as writers ourselves.

What is important I think, then, is to offer student writers different opportunities and genres of writing so that they can apply this “choice-based” metacognition in as many different contexts as possible.

The examples that I’ve posted throughout this piece, for example, mainly came from a “flash fiction” project that we spent one week completing between units, followed by a peer-reflection workshop where they observed, analyzed, and celebrated—wait for it—the choices made by their peers.

So even in a course that has a rather heavy emphasis on literary analysis writing, we are intentionally creating space for other genres of writing for a host of reasons, with a core rationale being how it improves metacognitive writing itself.

For example, here is the template students will get next week for their narrative poems:

Once again, I try to be as consistent as possible at building space for metacognitive self-reflection into each writing process—with this upcoming one having a two-part aspect that aligns with our method of poetry analysis (emphasizing language and structure) and asks them to make visible the choices in the poems themselves.

So yes, this is about buying in as a teacher and building the self-reflection into the writing process, but I think it also matters that you are affording students different genres of writing to self-reflect upon.

Why Does This Matter?

In a world in which artificial writing will become more and more widespread, likely, as the technology advances—which Jim and I discussed on the latest episode of our podcast—the ability of students to have an authentic, deep grasp of their own role crafting their original writing matters that much more.

Even in writing this post, there are so many choices I’ve made, after all, from where to begin/end sections, how many student examples to include visually, and when the time was right to reflect on my own belief as far as the significance of metacognition.

This is what we do when we write, all of us.

The problem is that this choice-making is far, far too often invisible to students—even from us as teachers who very much want to model best practices in our own work!—and therefore the solution, I believe, is to make it visible and tangible in as many ways as possible.

So now when I write exemplars, I try to make sure also to include exemplar self-reflection, modeling the priority that I believe it should be and giving clear examples of how even experienced writers still very much make and struggle with these choices.

We all make choices when we write, so let’s lean into them in our classes—which begins with creating space for students to name and reflect on them consistently.

On a separate note, I hope everyone is having a good start to their December experience—which can be turbulent and tedious all at once, along with very tiring!

If there’s ever a topic you’d like these posts to tackle or that you’d like Jim and I to deal with on the podcast, don’t hesitate to reach out. And of course, we always appreciate when you subscribe and/or share!

More than anything, though, I want to express my appreciation for you taking the time to read this and engage with the pedagogical conversations we need to have more in education. Answers aside, more conversations need to be had by as many stakeholders as possible, so thank you for investing your own time to read this piece!

Take care, and good luck in this final stretch before Winter Break.

—Marcus

I tried this with my students this week and it was amazing! I loved hearing why they made the writing choices they did.

Can you tell me more about the 75% threshold? How does that work in your class?