A Space Between Fear and Hope

a reflection building from the 5th chapter of our Fall Book Study

This week happened. We all know it. And particularly as educators, we know the stakes—especially for our students and their families.

The right path moving forward? Not so clear.

This is why I was so grateful to read and reflect on Chapter 5 of

’s Becoming an Everyday Changemaker this week. (Note for new folks: if you’re interested, you can follow along our journey through this incredible book here with links to each week’s post and conversation.)This chapter spoke to this moment for me with a particular clarity and resonance—which is what I’m going to share about in today’s reflection.

First, though, a brief summary of the latest chapter:

Chapter 5 Summary: the second part of this book begins with a shift to skills necessary for educators to successfully navigate the journey towards equitable change, and the first one Venet focuses on is, in my opinion, essential: both/and thinking.

As opposed to “either/or binary approaches” (97) and “false dichotomies” (98), Venet offers a both/and mindset in Chapter 5 that lives within the many tensions of education and leans into these complexities fully rather than resisting them.

After also acknowledging the difficulty of this type of thinking, in Chapter 5 Venet ends by affirming its importance and offering a tool for practice: Vent diagrams, which I’ll dive into in my reflection below.

If you’re like me, you took a deep breath before stepping, or maybe tiptoeing, into the classroom on Wednesday.

The classroom is always quiet when you first enter before students arrive, but this past Wednesday? There was somehow a silence inside that quiet.

I’m not going to pretend to have certainty around the implications for education as a result of the 2024 US Presidential Election, but I’m also not going to pretend that we can draw even a semblance of a line between the political happenings of this week and the lived experiences of students and teachers alike.

Fear of losing family members for many students just became more real. Fear of losing protections as already-targeted students just became more real. And fear of schools having fewer resources to fully see and support their students just became more real, too.

As Zora Neale Hurston presciently wrote, “fear is the most divine emotion.” (Yes, that was quite a line to end with this week in the classroom. The right line, too.)

Yet after that deep breath—well, really, several deep breaths, if I’m being honest—I did step into the classroom and found myself immediately grateful for that classroom, more than anything for the students who showed up that day as they always do: with joy and resilience and purpose.

I walked out of the classroom Wednesday still mindful of those reasons for fear.

But I also walked out hopeful—and struggling to reconcile the hope I found in the laughter and purpose of the classroom with the very-real fear in the contexts swirling around it.

How am I laughing right now? I thought to myself several times on Wednesday, and then again on Thursday and Friday. I love the joy of this room, but am I just sticking my head in the sand if I choose to lean into it right now?

That ongoing internal struggle of trying to decide between fear and hope then collided directly with Venet’s fifth chapter, starting with this line:

Reminder-to-self: the classroom was already messy and therefore the work of being in that classroom is messy—and it is about to become that much messier.

As Venet rightly observes, this is why adopting a both/and mindset as we navigate that mess as educators has never been more important: “Both/and thinking helps us to break out of entrenched ideas, honor multiple perspectives, and move forward creatively” (96).

Plus, I’d offer that most of us already know the importance of this type of thinking. After all, our work in education—especially as classroom teachers—is rife with not just contradictions but paradoxes aplenty:

How do I create a classroom that is flexible and responsive to student voice over the year while also making sure it is a reliable, consistent environment for students who need that structure?

How do I invest what is needed to make the classroom everything that students need it to be while also not overextending myself to the point I become burned out as a teacher?

How do I prepare students to successfully navigate the expectations and assessments of our current education system while also harnessing their creativity and imagining what potential could exist beyond those limitations?

Indeed, to be a teacher and to work in education is to swim in the waters of paradox, a frustrating and riveting and exhausting journey that can both bring out our best and leave us overwhelmed. We all do that swimming daily, within our classrooms and outside of them. We know these waters well.

Then this week happened.

This is the moment in the chapter that took my breath away, especially as Venet follows it up with the analogy of all analogies for this exact moment: “I lost my flashlight in the dark and I can’t find it without my flashlight” (102).

Many of us have been grasping around in the dark without flashlights this week, understandably, and what Venet notes here is what I’m sitting with most of all: it takes a lot to hold onto a both/and mindset when we’re struggling, even as we need that both/and mindset to confront that very struggle.

And when our tanks are empty? That is when we fall into the either/or thinking, when we give up on the complexities that education is rife with and pick a side rather than straddle the complexities that need to be straddled, enduring the “internal friction” Venet notes is necessary for this type of work (102).

Going back to how I felt walking out of my classroom on Wednesday with a nearly-empty tank (and again Thursday, and again Friday), either/or thinking would have meant choosing between these two options:

Focusing on the fear and frustration of the potential consequences of this election for students and our broader education community—but missing out on the good still very much there in the classroom.

Focusing solely on that good in the classroom—but choosing to ignore the very-real contexts and implications that will need to be considered and responded to in the years ahead.

That’s not just an either/or. That’s also a lose/lose scenario.

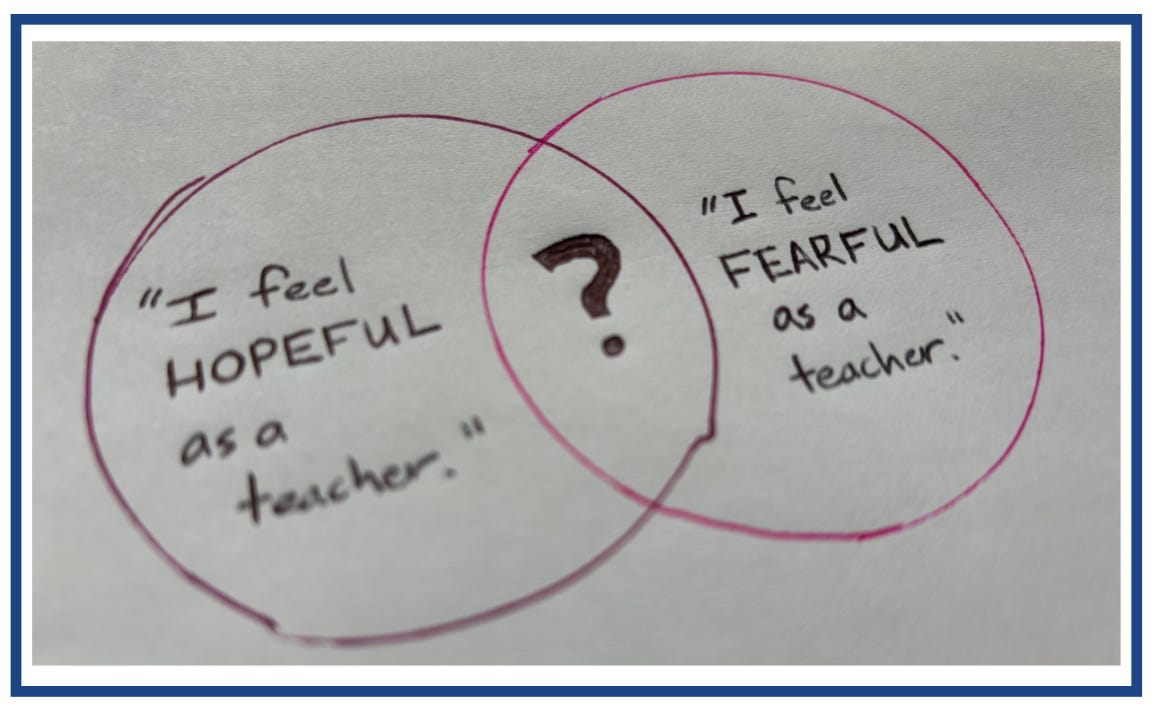

So I turned to the final activity that Venet offers in this chapter: Vent diagrams.

In her canonical sociology book Purity and Danger, Mary Douglas noted the importance of spaces of tension that Venet centers the chapter around, these margins, as well as their stakes: “To have been in the margins is to have been in contact with danger, to have been at a source of power.”

The concept of Vent Diagrams—in which you “purposefully don’t label the overlapping middle”—is to, in the words of the creators, “recognize and reckon with contradictions and keep imagining and acting from the intersections and overlaps.”

I’m not going to lie: writing down “I feel hopeful as a teacher” and then writing down “I feel fearful as a teacher” and then staring at the center? And ultimately shading in a big, fat question mark in the middle?

It felt like the only thing to do at this moment.

For me, labeling this diagram became a sort of permission structure for my hope, which even if wavering and fragile still is present and, at times, vibrant. In my experience, there are few places more hopeful than a classroom, at least when you’re willing to look for it.

At the same time, this diagram also reminded me that the reason for fear is very real, and more importantly that the temptation to tell myself a story of reassurance—particularly as a white, cis-gendered male educator—is one that neglects the looming contexts that threaten so many of students and other teachers.

That space between hope and fear, then? I believe it will matter more than ever in the years ahead, even as it is likely going to become more challenging than ever to live in that margin as educators.

That is where the power is, though, Douglas reminds us.

And also the empowerment. For us and the students in our classrooms.

Let’s commit to living in that space between hope and fear, therefore, as well as the both/and mindset required to honor that commitment—and let’s make sure we are supporting each other in that commitment going forward.

That’s the only path I can imagine working right now.

Feel free to respond to the discussion questions above about Chapter 5, or to pose your own questions, too! (Reminder: you do not need to have a Substack account or subscribe to join the conversation.)

See you in the comments—and then next week at Adrian’s Newsletter to talk about the sixth chapter of this book!

Finally, some additional updates

Before signing off, especially given the importance of community in this moment as we move forward as educators, I wanted to end with a few notes on where we’re at with The Broken Copier:

At this point, the negatives far outweigh the positives when it comes to our presence on Twitter, so aside from sharing out new posts both @MarcusLuther6 and @thebrokencopier will be mostly silent on there for the time being.

This is another paradox for us, of course, as the education community on Twitter is a large part of what has fueled the growth of The Broken Copier that we are truly grateful for—but right now we want to direct our community-building focus elsewhere. Context matters, after all, and Twitter has become a pretty dark context to build anything worth building.

That elsewhere? Well, for one, here—and a huge thank you to those who continue to read, subscribe, and share as the growth of this Substack leaves us repeatedly humbled!—but also over at BlueSky, where I’ll be sharing my normal classroom resources and thoughts far more regularly. (Note: if you’re looking for a a better online education community, I’d definitely try it out!)

There’s a lot of broken right now, and we are very grateful to have such a generous and insightful community with The Broken Copier to lean on as we figure out what the path ahead can look like in education. Let us know what you need from us, too, and most of all take care of yourselves.

Such a perfect description of how I felt this week as well.. filled with hope, joy and gratitude at the students and colleagues I work with, along with admiration at the human ability to be, well, human in the messy and the hard. The concept of both/and certainly comes into play in my role with student life. There is a need to have rules, structures that allow us to keep students safe and doing what they need to do at school. And there is also a need to understand where a student is coming from, why they made a decision or acted the way they did. And even in discussing consequences, both/and comes into play. There is both a consequence for this, and an understanding of where you are coming from and the work we need to do together moving forward.

One other comment about the work Venet shared about the boys and the misogynistic comments. This sentence on page 105, “If I focus only on the systemic thinking that the misogyny of teenage boys is preordained in a misogynistic society, I deny the agency of my students to change”. So many times in my career I have heard “boys will be boys” as an excuse for unkind or even aggressive behavior. And I always think, so they don’t have to change? Or even think about change? Or see options to behave differently? And the same could be said for the behaviors of girls that we accept as “typical teenage girl mean behavior”. To me, this sentence hit the nail right on the head.

I'm so honored and humbled to read your reflection of how this chapter resonated, especially this week. The question mark is a scary and generative place to be.