What does an A even mean?

building on a classroom conversation this week

There are many “conversations” in education.

Some better, some worse. None simple (even if we pretend otherwise), none isolated (even if we pretend otherwise). All cyclical, too, showing up again and again to flock towards the headline and generate debate—and the subsequent clicks that follow.

One of the most reliable of these “conversations” we keep finding ourselves having?

Students are getting too many A’s.

From what I can tell, the most recent iteration of this conversation that has emerged has been driven by two separate events: [1] a faculty report from Harvard about grade inflation and [2] a report from UC San Diego on “a steep decline in the academic preparation of its entering first-year students.”

Cue: internet outrage about the sky falling across academia.

Perhaps the most hyperbolic piece came from The Argument’s coverage of the UC San Diego report. I kid you not, these are actual quotes from that piece:

“I hope by now you are a tenth as infuriated on behalf of these students as I am.”

“To the high schools engaged in this fraud: It might temporarily make your statistics on how many students from disadvantaged backgrounds are taking calculus look a little better, but ultimately, it is an injustice to the very kids you’re claiming to help.”

“The only advice I can offer is this: Get angry.”

Reminder: if the only advice someone can offer is “get angry,” they probably aren’t the voice that we should gravitate our attention towards.

Unfortunately, though, if you write with outrage and hyperbole, instead of nuance and humility, in this moment you get rewarded—as this particular piece led to further coverage via Derek Thompson’s Plain English podcast with an episode titled “The American Math Crisis.”

And we’re off to the races with a tale as old as time, at least in this internet age.

Call it a crisis. Get clicks/downloads. Rinse/repeat.

Again, this is not a new conversation. Not even close to one. It is one that will continue to happen, though, perhaps with increasing volume but very little chance of a solution.

To be very clear: I don’t have one, either.

In today’s post, nevertheless, I want to offer something else that, in my view, has been glaringly absent from far too much of the coverage: an honest consideration what an A actually represents—especially in the eyes of students.

“Getting an A means…?”

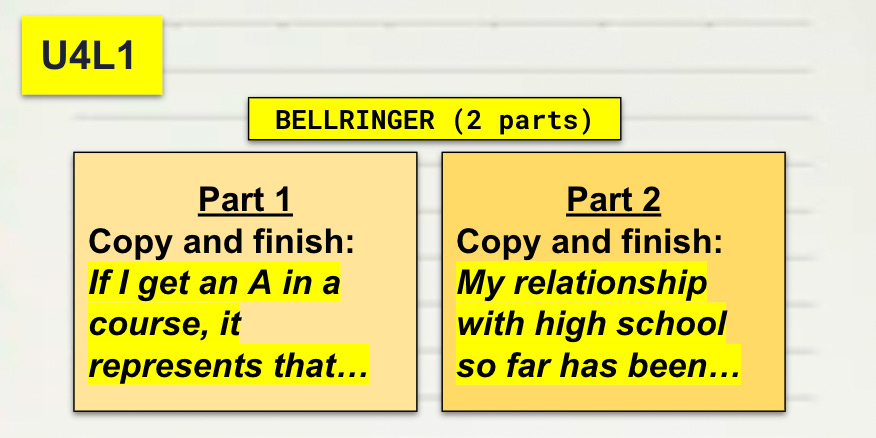

This past week, I posed a bellringer question leading into our reading and analysis of the late Louise Glück’s “The School Children” that asked my high school juniors to complete the following sentence:

If I get an A in a course, it represents that…

Students wrote their answers individually, conferred in small groups to arrive at some sort of consensus, and then shared out their answers while I recorded on the whiteboard.

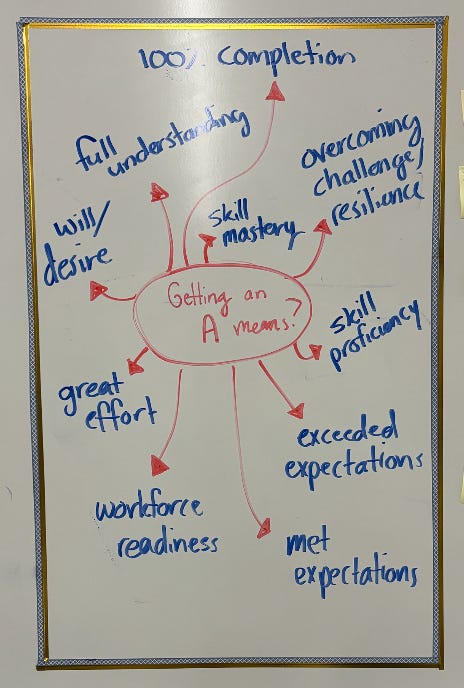

After three separate periods had completed this activity, I had tenfold collection of different answers (pictured above): [1] full understanding; [2] 100% completion; [3] skill mastery; [4] skill proficiency; [5] great effort; [6] will/desire; [7] met expectations; [8] exceeded expectations; [9] workforce readiness [!!!]; and [10] overcoming challenge/resilience.

“You’ve been getting grades for years,” I exclaimed to them as I jotted each down, “and we aren’t even close to having a definition in this room”

While we did debrief as a class for a bit, eventually we had to move onto the poem (really: it’s quite something!) yet I kept finding myself glancing back at that list on the whiteboard.

Considering all the different meanings students attach to getting an A.

Questions I don’t have an answer to (but are worth asking)

The best part about this exercise, which I try to do each year with my students students, is that it always raises far more questions than it answers—questions that, in my estimation, we need to do a much better job of answering.

These were just a few of the questions that I found myself reflecting on:

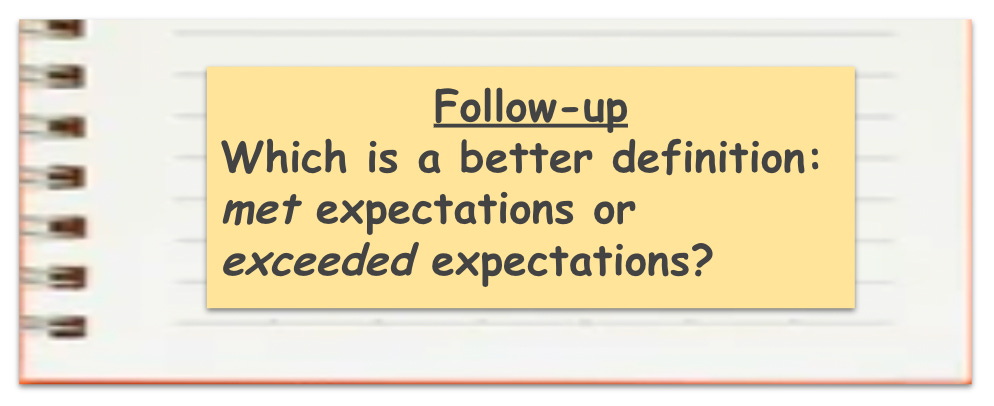

Met Expectations v. Exceeded Expectations? This is one that we actually discussed as a class afterwards, with the vote from students ending up almost precisely at 50/50 in all periods. No help, right? Perhaps. But rather than trying to reconcile that very-clear split amongst students, I actually found myself shifting to the latter word: Expectations. It seemed to speak to how external and inauthentic grades can feel, which is especially problematic when the goal of our work should be centered around learning.

Taking the “Great Effort” Answer Seriously. If I asked you to eliminate some of our classroom definitions from your personal answer to this question, I’d bet that “effort” might be one of the first to go. However, what I can “report back” from several years of asking this question in high school classrooms is that “effort” (along with “100% completion”) is consistently one of the most popular answers. Did they try their best and turn in all their work? A lot of students (and, I’d bet, families of students) believe that should result in an A grade. Don’t dismiss that.

Oh, and that other answer: “Workforce Readiness.” I will admit that I flinched a little when I heard the words, but then I thought back on the amount of times I’ve emphasized the purpose of what we were learning by framing it around situations and opportunities students could potentially encounter…in the workforce. I mean, just today I named the value of critical thinking in our work with a different poem as a skill employers increasingly value. So why am I surprised, then, when students associate an A with readiness for that workforce I keep talking about?

One more thing I’d add, too: this year was a relatively homogenous list, as in previous years I have seen answers like “happiness” alongside “playing the game” next to “making my parents proud” as well as “zero time for fun.”

If nothing else, it is not a simple definition.

(Also worth noting, I think: it never was.)

The other question we need to be asking, I think

Something I am very glad that I did with this activity this year, especially in hindsight, is to make it a two-part question. While the first part admittedly inspired this post, it was the second part that I think holds more gravity:

My relationship with high school so far has been…

The first step in our breaking down of any poem in our classroom is a thorough examination of its title before we launch forward, slowing down and brainstorming all the associations we can potentially attach to each part of it as well as the implications it might have for what we’re about to read.

Of course, “The School Children” is a relatively straightforward title.

Yet after some consideration and quiet reflection, the students erupted into potential interpretations within it, ranging from associations with innocence to questions about its formality.

Then one student offered the mic-drop observation I was hoping for:

“It’s like the children are defined by school itself.”

No one said anything after for a moment, but there was a lot of nodding.

I don’t have any definitional answers to the “conversation” around grades; and I certainly don’t presume to have figured out what grading policy serves students and their learning best.

What I do know? The experience of students and their journey as learners is tied, increasingly and often inextricably, to their relationship with grades and the policies we construct and enforce around them as teachers and educators.

I think we should be having more conversations around that instead.

Reader question: what do you think an A means?

I do believe this is a worthwhile exercise: if I gave you a blank slate to define what grades meant across our education system, how would you define what an A is?

Feel free to share in the comments, as it would be interesting to see what various readers feel—along with sharing any other reflections you have about how students experience grades/grading policies in our current system.

I teach at a fairly affluent school where a lot of students go on to prestigious colleges, and I've been told our average grade is now above 91. I am considered a "harsh" grader because my averages are usually in the B+ range.

Many of my students seem to feel that an A means that you worked hard and completed all the requirements. Many of them (and their parents) are also confused as to why a straight A transcript isn't enough to get them into Harvard or even, sometimes, into honors classes.

I like to have a little more spread in the grades because I want to incentivize excellence... It's hard to recognize when a student is doing really great work if everybody who meets the basic requirements gets the same grade.

I really wish we could lower the temperature around grades, because right now they aren't useful as information... Grades are not communicating much that's meaningful about students to parents, colleges, or the students themselves if everybody has straight As! But it's a classic collective action problem, and I don't know how it gets solved.

Such a good conversation! I have to admit being a little more worried about grade inflation than you are, but luckily I haven’t reached click-bait levels of panic yet, lol.