When You Ask Students What Their "Writing Story" Should Be Called

the culminating activity for our semester-long process of writing reflection

“Growth is Time”

“A Pebble in the Ocean”

“Writing Quickly, Slowly”

“The Rabbit Holes Are My Home”

“The ‘Not-So-Goldilocks’ Writer”

“What I Know”

These are just a handful of the myriad titles that students came up with for their own journey as writers over the first semester of our course—titles they then spent time explicating their thinking on and sharing aloud with our classroom community.

It was a really cool space to be in, needless to say.

All this after students annotated their own reflections that they have been compiling back since September (using the #TQE process that has been integrated into our learning all school year).

Take a look:

But Let’s Rewind: How Did We Get Here?

Over the summer, in reflecting on how I wanted our classroom community to be better this year, I came down to two main goals: 1) I wanted students to be more curious (hence, the #TQE investment that has been super impactful) and 2) I wanted students to walk away confident that they were better writers.

Reading through the end-of-course surveys from last year, I also recognized how fragmented the student experience can be for students as they juggle 7-8 classes, extracurricular activities, jobs, life itself, etc.

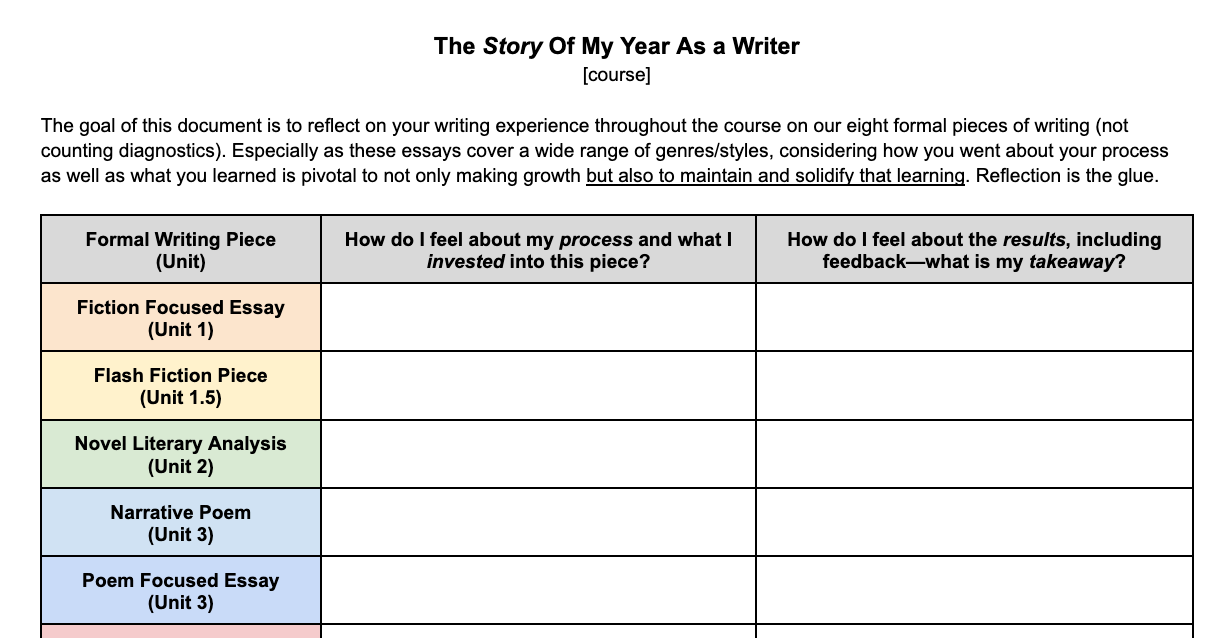

Even when our classroom learning was at its best, there were so many interruptions that made a consistent narrative difficult to establish. So in the second week of school, every student created this document to add to their course folder on Google Drive:

I wrote about this already in an earlier post, but the purpose was a) to center reflection on process alongside feedback and b) to create a document to serve as a “glue” for their learnings as writers as the year progressed.

And as the year moved on, these documents filled up in very meaningful ways:

And in watching each individual student’s document evolve with their reflections, I became that much more committed to the value of this system in our classroom community—and all others willing to give it a go, too. (Hence this post!)

Three Key Things In Making This Work

I could not be more enthusiastic about others establishing this system in their classroom (and here’s a link to a blank template, if that’s helpful), but I do think there were three important factors that helped make this system much more successful than it would have been otherwise:

Allocating Time For It. This system won’t work if it is just another “take care of this on your own time” activity. As I’ve become a broken record saying at this point (or—wait for it—broken copier, haha!) the way we allocate time in our classrooms is a direct reflection of what we value as teachers. So if you truly value reflection, you have to create time for it!

Establish a Debrief Process. For our classroom community, we go over whole-class averages and results, and then move into the major trends, both celebrations and growth areas, across the writings—and students individually reflect and then discuss in small groups a) which trend they felt their essay aligned with and b) what led them to that result. This builds investment in the feedback process and guides their focus as they move into the independent stage of it.

Offering Students Meaningful Feedback. This is the hardest part—and I don’t have a great solution—as far as the time it takes to give meaningful, precise feedback to students on their writing. 11 years into teaching English, I still believe that there has never been enough time in the day to do this well—and even typing this now I am feeling remnants of exhaustion for this final end-of-semester stretch of essay feedback. But it does matter, and I don’t think this system works without it.

What the End-of-Semester Activity Actually Looked Like:

Students arrived in class with a sheet of paper to record their debrief reflections on and immediately copied down our essential question for the day: Who am I right now as a writer and who do I want to become?

Then we moved into a two-part anticipation activity, with students reflecting and sharing their successes as well as growth areas (see one example above) along with going over class data—which I’d argue is key to the credibility of this exercise, too.

From there, students had dedicated time to add to their “Writing Story” documents while also reviewing previous reflections. Finally, they scrolled down to complete the new activity I had quickly added to each of their documents:

Our norm throughout the semester had been that close-reading is a way of acknowledging and affirming the value of a text—so why not take our #TQE close-reading process and apply it to their own reflections, right?

The room was pin-drop silent except for the click-clacking of keyboards, and you could see furrowed eyebrows from many students as they struggled for the perfect title to capture the writing journey they had been undertaking since the beginning of Semester (especially knowing they’d be sharing these titles whole-class shortly).

[also: if you’re curious about what these completed documents look like, I have full samples here and here, in case you want to look closer at some end-products!]

And then the long-awaited culmination, and the final activity of an incredible semester with these students: computers closed, pencils down, students sharing their “Writing Story” titles one at a time with the entire classroom.

“Growth is Time”

“A Pebble in the Ocean”

“Writing Quickly, Slowly”

“The Rabbit Holes Are My Home”

“The ‘Not-So-Goldilocks’ Writer”

“What I Know”

A really cool space to be in, indeed.

What I Know (I Think)

…is that reflection is too rare in classrooms, especially around writing and especially around process.

Looking back on all these student reflections the past week, too, I realize that I’d much rather have fewer writing samples and more space for the type of reflection and discussion that students experienced, if I had to choose. The quantity far too often gets in the way of quality—not only in quality of student writing, but also the quality of teacher feedback.

And in this ChatGPT world we are entering into, shouldn’t reflection be that much more valuable—and consequently prioritized?

I think for almost all teachers, the answer is yes, resoundingly. So the next step is to bring a system for meaningful, connective reflection into your classroom and then to make the time for that system to thrive.

What I know? It’s worth it.