Why Lesson Design Matters

But also why it's way more complicated than any formula

…curriculum design remains curiously neglected in professional discourse, treated as someone else’s problem, a given rather than a variable

In a post last week, Carl Hendrick laid out the case for why curriculum design is a critical yet under-discussed facet of our education system. Hendrick’s own argument, as he posits near the end of his piece, is that student “effort and expectations are themselves shaped by the architecture within which they operate.”"

Immediately this resonated with me, as I also had been thinking quite a bit about the word design a lot this year already:

Without question, in my mind, architecture matters a great deal—not only across a curriculum but in each individual lesson.

To then shift our mindset as teachers, then, to own the potential impact (in either direction) of our design work?

That’s a big ask, a big shift, and a big responsibility.

Taking Responsibility for the Architecture

While I appreciate Hendrick’s emphasis on the impact of design, I admittedly resist the rigidity he envisions within it: “The best curricula, like the best watches, are designed so that component skills can be mastered to the point of automaticity before being combined.”

I read that sentence as a Year-14 ELA teacher and flinch.

Automacity?

It’s way more complicated than that.

However, to be clear: I’m just as averse to teachers using “it's way more complicated” as a shield from responsibility for the learning in their classroom.

We are responsible for how we design the learning in our classroom, especially in how we craft individual lessons.

Matt Brady’s post this week that echoes this sentiment about the importance of lesson design: “Because if I’m not responsible for a student’s identity, I am responsible for the architecture around it.”

There’s that architecture word again—and I could not agree more with this overarching mindset: how we craft our curriculum sequence and the individual lessons within it matters—it matters a great deal.

Design Choices From The Classroom

One of my intentions for 2026 with The Broken Copier is to continue leaning into what is most authentic to my lived experience as a classroom teacher: sharing actual examples from my classroom alongside reflections on what I’ve learned from these experiences.

So for today’s post, I want to present a “design scenario” that has long been one of my most frustrating: what to do with the first lesson returning from an extended break?

This is doubly-challenging in my current context, as Monday lessons are much shorter (just over forty minutes instead of our normal rotating block periods the rest of the week) and, in this particular case, we only had a few weeks left in the semester.

However, in both my English 10 and AP Literature courses, for once I felt really good about what happened in our classroom that first day back from Winter Break—so I want to share the choices I made here with both these lesson designs along with some after-the-fact reflection (and video explainers that go more into detail for each).

What We Did With English 10

Context: this on-level sophomore English class was midway through our reading of Trevor Noah’s Born a Crime, having just completed an in-class writing assessment on complex characterization before Winter Break—and with only a few weeks to before the semester ends, including our concluding Socratic Seminar.

The Priorities: strike a balance between community and urgency (only three weeks left in the semester!) along with a lesson design that meets the needs of students at very different places (those who scored well on the writing assessment versus those who struggled versus those who were absent the final week and did not complete it yet).

What I Chose To Do: the video above walks through the full lesson (slide deck here), but here is your brief rundown:

Opening SLIME bellringer (tangentially aligned with focus skill), along with students sharing which of the five options they wrote about whole-class followed by a group debrief of their answers

Overview of most common writing assessment feedback I provided, with students writing these down in their spiral to prepare for gallery walk activity

Student “feedback matching” gallery walk, as they moved around the room to read through sample assessments and pair the correct feedback with each (Note: this activity has been awesome this year! Very much recommend.)

Whole-class debrief of the “correct matchings” along with self-reflection: which feedback do you think yours got?

Individual student feedback check along with naming of their “next steps” on a sticky note exit ticket so I can track who intends to do what—and then a concluding skill review using the opening bellringer.

What Went Really Well? This lesson resulted in one of the highest rates of quiz revision and conferencing I’ve had all year with sophomores. It welcomed students back into the classroom without forfeiting urgency, and did so in the shortest lesson frame of the week for me.

Looking Back, What Would I Change? Though navigating the shorter time frame of the Monday lesson is tricky, I think I would have added a mini-sequence for me to walk through what the constructed response quiz before Winter Break entailed step-by-step—both to help bring it back to the forefront for students who took it and to give additional context for those who may have been absent. I think the current design relied on the feedback activity to do that work, and it would have been worth it to provide more direct explanation around it first.

What We Did With AP Literature

Context: this AP Literature course is full of juniors, with 30+ students in each section, and at this point we were in the middle of our poetry analysis unit—with their end-of-semester in-class essay coming just two weeks. Our focus before Winter Break had been more about strategies for annotating and interpreting poems, too, so in this final stretch I needed to shift to a priority around written analysis—and to make that shift quickly.

The Priorities: similar to English 10, I wanted to reaffirm our community but I also needed to center practice opportunities for written analysis of their poetry interpretations.

What I Chose To Do: once again, the video above walks through the full lesson (slide deck here), but here is your brief rundown:

Opening short-term calendar overview (to calm and appease these very-busy juniors!) before diving into a warm-up poem to get back into our poetry close-reading

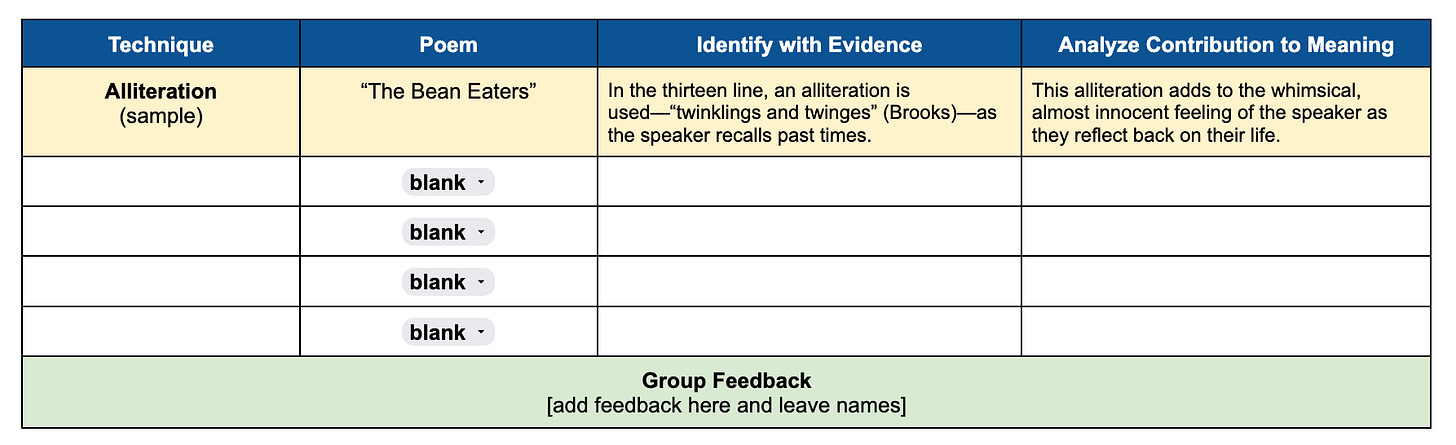

Skill review activity from before Winter Break: independently identifying and explaining an literary element/technique from one of the poems we already covered—which gave students a chance to engage with their notes and work from the initial half of the unit. (And, as a result, bring that learning out of Winter Break hibernation!)

Group shares and collaboration: students hopped on Chromebooks and had to work together to complete a digital task that transferred their independent work to a shared Google Doc and collaborate to create an additional element/technique analysis together before submitting.

We ran out of time at this point—those darned short Monday lessons!—so I ended up having them open this up the very next lesson to review/revise and then share their document with another group for feedback.

What Went Really Well? The reversed sequence of independent work (“You Do”) by students reviewing and applying skills from before Winter Break and group work (“We Do”) on the digital tool. I think this is a reminder, too, that sometimes we have to be open-minded about the sequence of how students learn in a given lesson design.

Looking Back, What Would I Change? I mean, as I’ve already admitted, I ran out of time! So I think the adjustment would have been to make that more proactively rather than having to pivot on the spot—which would mean building in a point of individual reflection at the end of the lesson for students rather than just letting them know that we would finish it the next class. Easy fix for the future!

Complications I Consider With Lesson Design

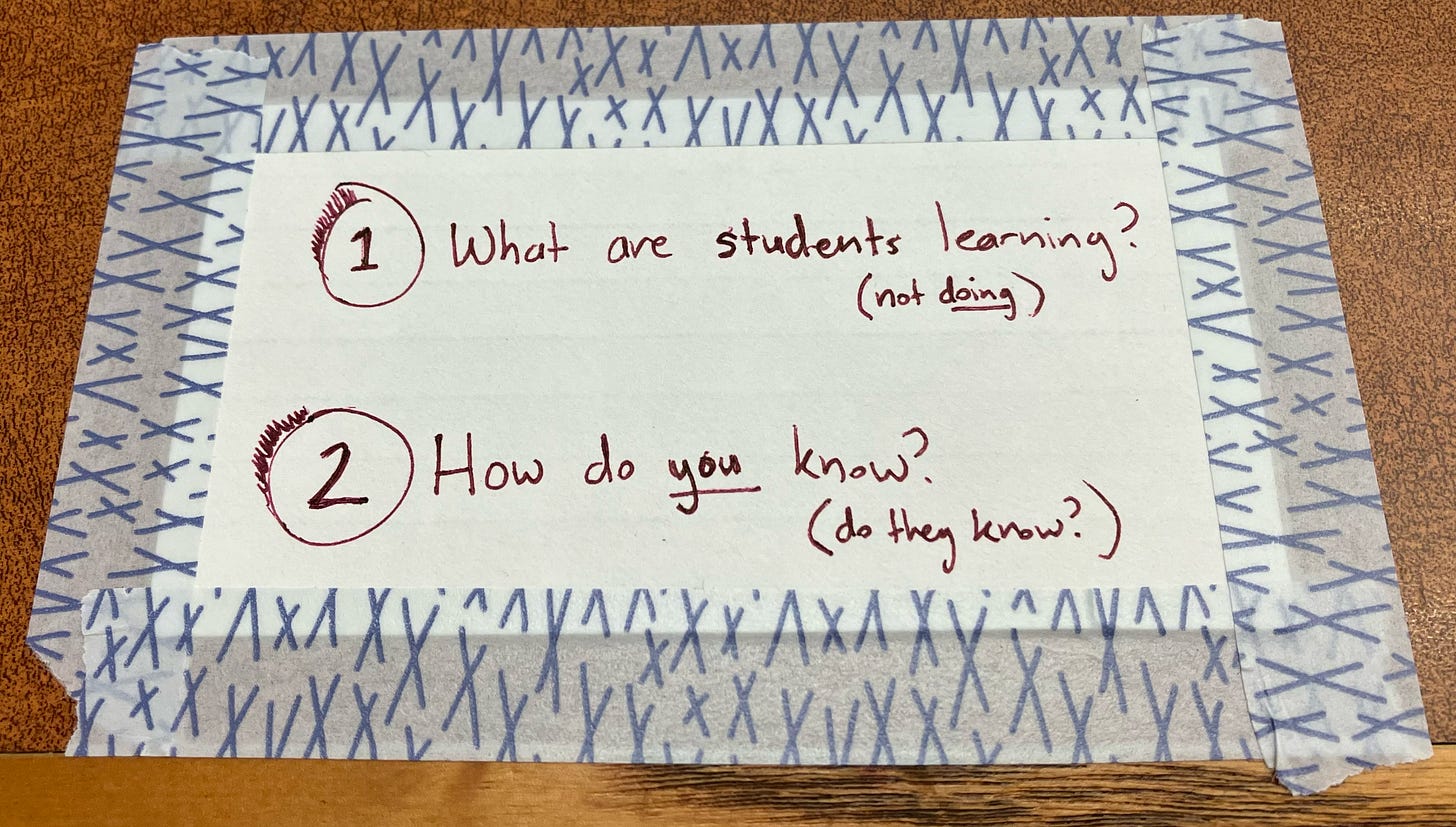

For a few years, I’ve had a simple, two-question placard affixed to my teaching desk: “[1] What are students learning and [2] How do you know?”

I continue to believe this is paramount for every teacher, every lesson—but, as already stated, I also think it is more complicated than that. So along with the reflections above, I want to zoom out and share three “complications” that I find myself weighing and reconfiguring constantly around lesson design:

3 Lesson Design Complications

I Do-We Do-You Do—but not necessarily in that order: Look, if the traditional gradual release model works for your classroom, go for it! As an ELA teacher, though, I rarely feel like that cleanly fits the needs of our classroom. However, that doesn’t mean that I am not constantly thinking about where and how the learning is happening in the classroom. This is why I genuinely appreciated Leah Mermelstein’s point on Teachers on Fire Substack this weekend: “it sounds like we go in this straight line, and then everything magically is impactful.” In the conversation, Mermelstein pointed out how there needn’t be a fixed order or sequence, and that the needs of the classroom are “messy”—so we need to respond flexibly and creatively to that tension. (Seriously: go listen to the full conversation if you haven’t! yet)

The Momentum Consideration: As someone who teaches on a modified block schedule, I see students either Monday-Tuesday-Thursday or Monday-Wednesday-Friday, and that’s presuming perfect attendance. This means that I give a lot of weight to something that a lot of lesson design models do little to account for: the momentum of the learning in our classroom, both within the class period as well as across periods. As Rod J. Naquin adeptly noted in his most recently, “teaching demands attention to far more than reformers typically acknowledge: not just content and engagement but also lesson momentum, classroom community, behavioral norms, and teachers’ own needs for order and calm.” With the lessons I shared in today’s post, I had to think about momentum a lot in both directions—how to create new momentum coming out of Winter Break as well as how to continue it with purpose and urgency forward in our final weeks of the semester.

The Right Role of Technology? I wrote about this more extensively in December, but I continue to feel that tension around the right use of technology in the classroom. Consequently, for every lesson, this is yet another consideration I have to make: what is gained by bringing technology into the design—and also what is lost? There are no easy answers, and this is why discernment continues to be a word I come back to repeatedly of late. (I’m also really excited to be presenting about seeking out a both/and with technology and collaboration in my classroom at IDEAcon next month!)

(An additional note: there are certainly so many other considerations that take place, too, from how to meet individual student needs, provide targeted and impactful scaffolds, prepare for absences and other extenuating circumstances, etc. What I’ve shared here isn’t at all meant to be an exhaustive list!)

One Other Question Worth Considering

The work of the teacher remains thus, forever, a frontier task. Always the teacher must deal with life at its point of becoming. —John Dewey

The Human Restoration Project’s Nick Covington shared this quote at the end of his reflective, hopeful piece yesterday: “We Are Worldbuilders”

Especially as I was arriving at final edits with this particular piece, Nick helped remind me about the essential role that imagination and hope play in this work—and the final question that deserves to be asked in every design process.

Why does this matter?

That does not mean that every single lesson needs to be transformational for students—and I don’t pretend for one second that the two lessons I shared in this post are transcendent or inspirational! (Indeed, the whole point of this post was to pick two normal lessons and talk through my thinking with them.)

Yet I think it is very much worth asking ourselves as teachers about the deeper, lasting purpose of every lesson we are imagining and designing for students—as any time we can lean into the ways in which the learning in our classroom translates beyond our classroom?

That is a good thing, and one worth considering and designing for whenever we can.

Every single lesson.

Reflection Questions to Consider

For those in the classroom: when you are designing your own lessons, what are the major considerations you make—and how have those considerations evolved over the years for you?

For those not in the classroom: when thinking about lesson design, what is something you wish more teachers weighed more heavily—and what are things you might not consider as much in not being in the classroom yourself?

Feel free to respond in the comments, and of course to check out some of the great posts I linked to across this post—as there has been so much great conversation and thinking going on about this important topic in recent weeks!

I really appreciated reading this piece—thank you for naming what matters so clearly. The question you ask—“What are kids learning, and how do you know?”—is so powerful and simple. I’d add another layer: “What are they confused about, and how do you know?” I’ve heard it suggested that a lesson can be designed so there are no confusions—and that’s crazy talk.

For me, what really matters is what we do with those confusions. I’ve found they can be untangled in different ways—sometimes in the next lesson, sometimes by adjusting how you approach the content the next time. That’s why I believe in teachers being prepared but not preplanned—noticing student learning and confusions fuels lessons naturally and makes the work lighter.

So many fancy papers, spreadsheets, and 300-page curricula can get in the way, and I really appreciate your clarity. Thanks also for the shoutout to my conversation with Tim! We need more of this dialogue and more voices like yours putting educators and researchers on equal footing.

I kinda hate that I'm saying this, but I've also started to take my own anticipated energy into lesson planning.

For example, if I have to run a high-energy classroom simulation for my 10th graders during 2nd period, I'll plan some low-key reading for my 12th graders during 3rd period.