Messy Scares Me (And That Might Be a Problem as a Teacher)

The opening reflection and question guide for our Fall Book Study!

Here we go! Today is the first post in our journey through ’s Becoming an Everyday Changemaker—a one-chapter-a-week discussion that we are co-hosting with via alternating reflections on our respective Substacks. (The post on the second chapter will go out through Adrian’s Newsletter, the third chapter here two weeks from today, etc.)

In each post, you’ll find a brief summary of the week’s chapter, a longer reflection from Adrian or myself, and then a series of discussion questions for everyone to engage with in the comments. You can follow along our journey through this incredible book here, too, with links to each week’s post and conversation.

(If you’re not participating in the book study, no worries! Though I think the reflection still might be worthwhile to consider, we’ll still be sharing out our normal The Broken Copier content, too, including another piece coming out later this week!)

What happened in Chapter 1?

Chapter 1 begins by presenting two different “changemakers” (Oriana and Drew) with quite-different contexts, and then moves into what Venet refers to as “the tensions of change.”

Grounding the book with an emphasis on the process of change—”How we move through school change matters” (18)—Venet invites a consideration of not only how change can be challenging for those pursuing it but also those experiencing it, particularly through the lens of trauma.

This is why Venet invites and advocates for a process-focus for us as educators, arguing that “[w]e may not find a single, clear answer to the contradictions of change, but by focusing on the process, we can find a path forward” (25).

I’m not going to lie: I opened this book thinking about change outside of my classroom.

The reason I did this? I feel pretty good right now about what is happening within the four walls of my classroom.

At this point in Year 13, I feel like I have made a lot of intentional choices to not only elevate instruction but to also prioritize classroom community. As I wrote about at the end of last school year, the classroom can be a really cool place—and I feel like mine is most of the time!

I am confident about what the classroom needs to be to begin each school year and I do a lot of work to make sure that I’m prepared to start that work with students by the first day they walk in—that way we don’t have to waste any time building the community I believe is possible by the end of the year.

So it’s the change outside of my classroom that needs to happen. Right?

Then I read Chapter 1—and almost literally felt Alex grabbing me by the shoulders and shaking me out of my blissful, potentially-problematic assumptions about my own classroom and the control I too often take as the teacher within it.

On page 18, she shares a hypothetical in which a school decides to revise a policy around a dress code to prioritize equity. A noble intention, but Alex’s point here is that even if the administrators made the right call, doing so without authentic collaboration with the voices of stakeholders “leaves inequitable power dynamics in place.”

For me, this took me right back into my room—the one I feel so good about, remember!—and how I choose to begin the school year making so many choices for the classroom without any input from students within it.

As a result? Chapter 1 helped me realize the inside of my classroom needs work, too, and that it’s 100% on me to continue pursuing that work with a process-lens.

Now, I I think I understand why I begin the school year the way I do.

One thing that has been hammered into me as a teacher throughout my career is the importance of having a strong, consistent foundation to begin any school year.

In my eyes, this includes the systems and structures that students walk into Day 1, from our policies to our classroom routines to our community values. Given that I have 200+ students across the different courses and class periods I teach, that is way too messy to facilitate an organic process to invite students to create their own policies and routines and values.

This is where this book immediately is pushing me towards important reflection:

Why do I cling to the control that I do, particularly at the beginning of the year?

What are the consequences of me choosing not to release more of that control and engage with the messiness that is a more-authentic process towards student voice and change to build our classroom?

While I know my own surface-level answers to these questions, Chapter 1 of Becoming an Everyday Changemaker immediately challenged some of my assumptions in a meaningful, important way—forcing me to reflect on my own reticence towards “messy” and how I might be overlooking the value of a process-focused lens into my own classroom.

No matter my conviction in a given outcome.

That is why I’m sitting with this question from Alex on page 25 so much this week: “How can I navigate the tension between the ned for change and the importance of the process?”

While I do want to continue pursuing change beyond my classroom, I am also reminded that there is plenty of change needed within my four walls as a teacher, too.

(And this is just Chapter 1!)

So, what did everyone else think about Chapter 1?

If you’re reading along with us, we highly encourage you to jump into the comments to share your own reaction—what did you think of the opening chapter of this book and how did it resonate with your own experience?

Feel free to respond to the discussion questions above, or to pose your own questions, too! (Reminder: you do not need to have a Substack account or subscribe to join the conversation.) You can go ahead and share this post out to anyone else you think might enjoy the conversation, too!

See you in the comments—and then next week at Adrian’s Newsletter to talk about the second chapter of this book!

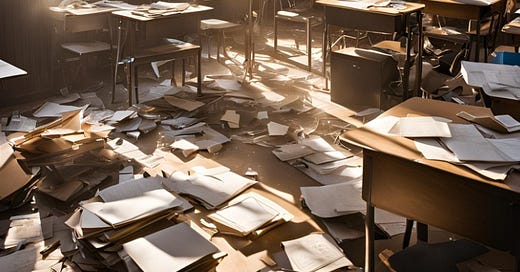

Note: thumbnail image generated by Canva AI through the prompt “messy high school classroom” (baby steps for me, right?)

The biggest barrier I face when advocating for teaching with a process lens, is sustainability. It is easy after decades in the classroom, fighting for a more just and equitable public education system, to begin feeling demoralized and burned out. Just like Ursula Wolfe-Rocca tweeted, all of the injustices are overwhelming! I take solace in pulling at my own thread, while challenging myself to be more present with the changes needed outside of my classroom. This slow-read book study is helping to reinvigorate my changemaker spirit, meeting like-minded educators and other stakeholders who are working toward a better future. I love Grace Lee Boggs' quote, "groups of people of all kinds and all ages to participate in creating a vision of the future that willenlage the humanity of all of us" (p. 26). I believe that is what I am trying to do in my school building and what we are doing here with discussing this book.

Reading this chapter, I’m flooded with memories from so many spaces in my 30+ year career as a public school educator. Teacher, department and grade-level chair, mentor teacher, small school director, AP in a large school, central admin roles including multiple roles in professional development with varying levels of remit and scope. I’m struck by how rarely I’ve worked with leaders who really understood how to lead adults in investigating their practices, letting go of what wasn’t working, and taking up some new practices that work better. I’ve had even fewer experiences where leaders led a group of adults in collaboratively investigating old practices and taking up new ones. My Critical Friends Group experiences were probably the closest.

At Alex’s first rest stop on page 22, I’m met with sadness. I think the large majority of adults in meta- and micro-cultures in which I’ve worked as an educator have not done much work to understand their own trauma and oppression and how they repeat those patterns in traumatizing and oppressing kids. It’s not just leaders enacting oppressive behaviors and beliefs on staff and children. It’s staff enacting oppressive behaviors and beliefs on children and each other. And children enacting oppressive behaviors and beliefs on vulnerable peers. The group dynamics in nested bureaucratic hierarchies (classrooms within departments within schools within districts within states) compound these tendencies. (A friend told me last week that Jung refused to work with groups because of this dynamic — I can’t verify this but … whoa.)

I’ve sat in trauma-informed instruction sessions at schools and district leadership institutes that were so oblivious and ham-handed that I experienced re-traumatizing. I’ve walked many schools with leaders and on my own and have been stunned by the number and variety of micro- and macro-aggressions I witnessed. I can see more and more clearly as the years wear on why change initiatives in schools and districts so often fail to influence thinking and practice in the intended way.

The kind of classroom Adrian and Marcus seek to create are rare in my experience. I think we who are on the tail of the bell curve can see our sole responsibility as remaking our spaces (classroom and heart) into havens, but I think we have to be brave enough too to seek to influence our peers and administrators too. It’s so hard because we have to hold the mean teacher in our heart, and the one who badmouths kids, and the one whose instruction is inept, and the one who complains about any new initiative, and the one who talks through PD, and the one who gossips about your peers. Just like our students, we have to see them and empathize with them in order to address their concerns and meet their needs.