How Students See Their Own Learning

a reflective tool and system that can change how you understand your students

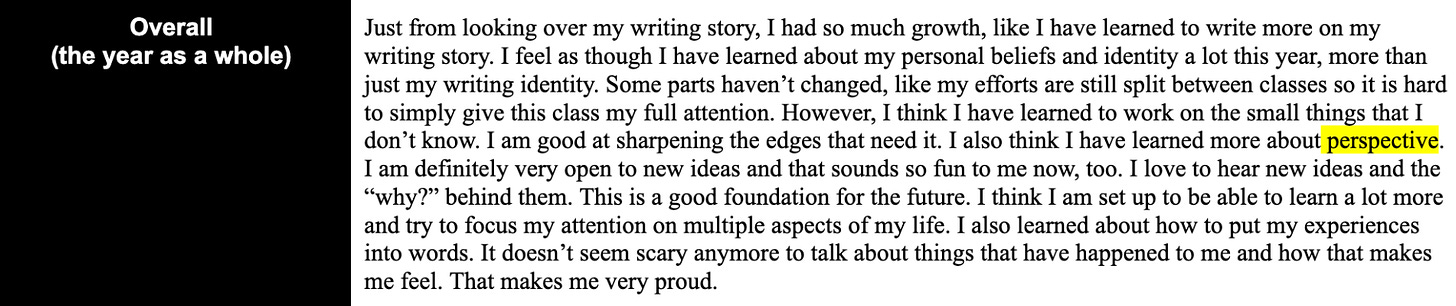

A few years back, I had a student who was on a consistent, impressive trajectory of growth. Over our four major writing opportunities, they had made clear strides at each point—and by the end of the semester, had one of the top performances in the entire class.

On paper? A clear story of success.

In a classroom with 30+ students, looking at the numbers this student was not one to be concerned about as a teacher. All the evidence indicated that they were improving substantially as a writer even as the rigor of the texts increased.

Well, most of the evidence.

In our classroom, I have one other lens of evidence when it comes to student writing: their ongoing “Writing Story” document, in which they record a self-reflection before they submit each writing task as well as after they receive feedback—and when I opened up this student’s post-feedback reflection expecting to read about their pride and confidence, I saw something completely different:

Dang. They wrote. I really thought I did better this time. I know there is always going to be constructive criticism but sometimes I have a hard time taking it, and this is one of those times

My perspective of how this student was doing? Completely different from their perspective of their own learning and progress.

And something that needed to be addressed.

A Learning Story Document

I’ve mentioned this tool several times over the last few years and written about it more extensively at The Cult of Pedagogy, but going into this school year I felt like I wanted to make the case here for not just what and how this document lives in our classroom but also why I think it matters more than ever.

But first: what is a “learning story” document? (quick note: as an English teacher, I call this a “Writing Story” in our room but without question it could be used for any content area!)

Each student has their own Google Doc digital template (pictured above) that they update throughout the school year after each assessment.

Before they receive feedback, they reflect on their process and how they feel about their work

Then at the end of our collective feedback lesson, students return to the document after receiving individual feedback to record their thinking and takeaways

Each assessment we go through the same process along with with reading back through what they’ve recorded in their prior reflections—and of course this system opens the door to so many conversations in our classroom! (Not to mention a fantastic tool for family conferences, I’d add.)

But before getting into more of the intricacies and things I’ve learned in using this system in recent years, here are some student samples along with templates in case you want to create your own:

Blank Template (“Assessment 1,” “Assessment 2,” etc.)

Completed Template (pictured above)

What I’ve Learned About This Tool

When I first created these documents and had students begin reflecting on them, it was a complete experiment.

I did not know what they would become in our classroom—or other classrooms, as I’ve now seen examples of them showing up in classrooms all over the past two years from generous folks willing to share how they have implemented and adapted this tool! (Seriously: that is 100% why we wanted to create The Broken Copier in the first place—so thank you to those who have reached out with samples of how you’ve used this.)

One of the reasons I wanted to write this specific post, though, was to share five learnings about how to make it as effective and meaningful as possible in the classroom from the past few years.

100% implementation at the beginning matters. Taking the time to make sure every single student has a document set-up is worth that time taken, especially after that first reflection opportunity. When you swim against the tide in your classroom (and I promise, centering reflection this much is indeed swimming against the tide!) then you need to make sure you have what it takes to sustain that trajectory, which begins with a commitment to a strong implementation.

Exemplar reflections can help a lot early on, too. I link multiple exemplar reflections to the individual templates and then also project them on the board the first few times we do this—including different types of responses that might help students figure out their own path. This also can be helpful after students have completed their first row in terms of having them read through the exemplar and consider how theirs compares (in terms of quantity as well as quality).

Students need to know that you read them as a teacher. A mistake I’ve made at times is just glancing through these reflections without slowing down to respond to them, which can signal to students that I don’t value them as much as I actually do. (In the video below, I also share about a negative experience when I missed something I should not have missed in one of these documents.) Something as simple as adding a comment on the document each time students complete a row of reflection can help reaffirm it’s value in your classroom—which is a reminder-to-self for me going into this new school year, too.

Reflections shouldn’t just live on the document. Yes, the quality of the written responses and the reflection within them matters! But what gets me so enthusiastic about this system are the conversations that happen in our classroom amongst students as a result of their written reflections. I mean, imagine a classroom full of students talking with each other about their own learning on a regular basis with increasing confidence—isn’t that what we want in all of our spaces?

Most powerful? Students reflecting on the document itself. The individual reflections matter for each assessment, but where I’ve seen this document emerge as the most important thing in our room is when I’ve prompted students to go back and read through their self-reflections as a stretch. Students notice patterns in their process as well as mindset (example: failing to take the time to revise, being consistently self-critical, etc.) as well as the ways they shift and grow over the school year—which leads to really cool epiphanies as these documents expand and evolve.

Along with these five learnings, I also recorded a video to elaborate a bit more while also walking through the tool itself. (Note: I am back to work officially this week and I think it is very clear watching this video that I am officially exhausted, too, one day in!)

“I forgot that I was proud of myself…”

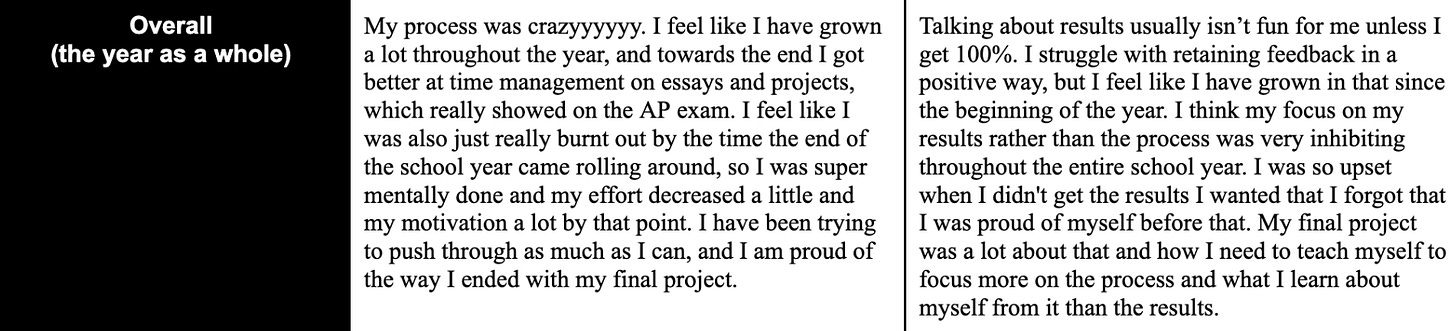

I do want to return to the student mentioned in the beginning of this post who was discouraged despite the significant growth they had made in terms with their scores.

Dang. I really thought I did better this time.

Reading that reflection led to an email to their family and scheduling an in-person conference after school to discuss this student’s mindset and overall perspective about school as they prepared to go into their last year of high school.

It was a really positive, important conversation—and I don’t believe it would have taken place without this reflection document.

The most frequent thing I tell people about implementing this system is that I feel like I now have a much better understanding of how the students in my classroom see themselves as learners, almost akin to the feeling I had when I first started wearing glasses and looked outside.

And realized what I had been missing before.

I was so upset when I didn’t get the results I wanted, this same student wrote in their end-of-year reflection on their Writing Story document, that I forgot that I was proud of myself before that.

One: what a joy it is to be a teacher and get a front row seat to a student’s journey through a classroom in their own words.

Two: for this and many other reasons, this system of reflection is a permanent fixture in our classroom.

A System For This Moment

At the end of our AP Literature course, students are asked to create a multi-genre project about what they find meaningful—and this past year I decided to create a new exemplar exploring my own story as a writer and teacher over the years.

Midway through, I wrote the following:

The foundation of what writing is? It is shifting. And what that means for the classroom?

I still don’t know.

Sharing that with students to end the year felt important as their teacher, particularly as I had cheered them on from my front row seat on their writing journeys.

Heading into this school year, I still very much don’t know—aside from the fact that this AI-generated abyss feels like it is getting more abyss-like, and abysmal, the more I read and understand.

What I do know, though?

That it has never been more important to slow down, to ask students to sit with their own words and to reflect on what they wrote and how they feel about what they wrote and, ultimately, what writing means to them overall. To have those conversations in the classroom with conviction in one hand and humility in the other.

To reflect, individually and then collectively, on where we go from here.

I started implementing this second semester last year with my middle school history classes. I LOVED IT!! Reading their reflections about different assignments was such a highlight for me, and also guided some of my future planning for units as well. One of the main things kids noticed about themselves was that the quality of their notes improved over time, since almost all of my assessments were open note. Such a joy. Thank you for sharing. Highly recommend.

This is great, Marcus. I'm reminded of a possibly misremembered line from The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony: "The gods become bored with people who have no stories." (And you really, really don't want to have the Greek gods getting bored with you...)

As it happens, I'm in the process of working over the Story of Your Project guide/tool that I use with my students. As the name suggests, the framing is somewhat different from what you're discussing here, though I think we're broadly working in the same direction.

One thing that can be really helpful about the Story approach: thinking about learning as a story offers an intuitive way of understanding the value of difficulty. A good story has conflict, questioning, struggle, uncertainty. ("Everything went smoothly and I was right the whole time" is not a good story.) When we encourage our students to think about learning as a story, we can offer students a way of recognizing the value of experiences they've often been trained to see as negative: not knowing the answer, realizing you were wrong, trying something that didn't work out, etc.

That being said, one challenge I've encountered with this kind of reflective writing is that it can sometimes become performative. Students sometimes think that they know the kind of story you want to hear and they just give you that. I'm curious if this is something that you've run into and if so how you've navigated it.